Correction: Bracha was Exactly Correct about the Privy Council Exception

Patent – Patently-O 2017-08-24

by Dennis Crouch

In an earlier post, I commented on what I suggested was an error by Professor Oren Bracha in his SJD Thesis Owning Ideas: A History of Anglo-American Intellectual Property. On further reflection – Bracha was not wrong, but exactly correct.

Bracha’s work cited a 1904 treatise on English Patent Law as stating that “revocation clauses authorizing the Privy Council to revoke patents were continued to be inserted in the patent grants up to 1902.” Although the 1904 treatise itself is somewhat cryptic, the 1852 patent law sets out a “statutory form” for a patent right that includes the caveat for the privy counsel (or the queen herself) to void the patent if it turns out it was improperly issued or becomes “prejudicial or inconvenient.” The form indicates the following statement should be included with each patent grant:

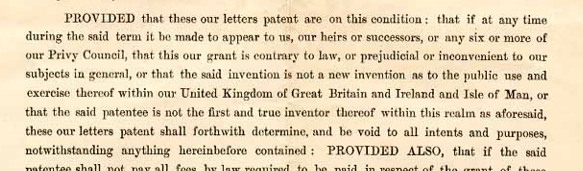

Provided always, and these Our Letters Patent are and shall be upon this Condition, that if at any Time during the said Term hereby granted it shall be made appear to Us, Our Heirs or Successors, or any Six or more of Our or their Privy Council, that this Our Grant is contrary to Law, or prejudicial or inconvenient to Our subjects in general, or that the said Invention is not a new Invention as to the public Use and Exercise thereof, or that the said is not the true and first Inventor thereof within this Realm as aforesaid, these Our Letters Patent shall forthwith cease, determine, and be utterly void to all Intents and Purposes, anything herein before contained to the contrary thereof in anywise notwithstanding.

Patent Law Amendment Act of 1852 [PL Amendment Act (1852)].

The historic point here – although the it did not actually revoke any patents after 1779 — the privy council seemingly held that power up until at least 1902.

I only had a chance to look through one English patent issued during this time period – the 1896 Marconi patent. The patent does include the caveat that permits the Privy Council to void the patent – following the form language almost identically.

Thank you to Professors John Golden and Oren Bracha for providing copies of these historic references and pointing out my error.

= = =

Applying it to Oil States: When the US was formed, we rejected the notion of royalty and the surrounding apparatus (including a privy council). So, in my view, there is not a direct line of reasoning that somehow transfers the privy council power to the PTO or even to Congress to distribute as it wishes. Rather, the way that I think about the privy council issue in relation to Oil States is to focus on the question of whether administrative revocation somehow offends our American court structure and its place within the federal government. I can imagine the Supreme Court writing something along the lines of: “Even in England, at the heyday of common law courts, patents could be administratively cancelled upon private petition.” Under this interpretation privy council supports the PTO’s power to revoke.

There is a flip-side argument here that might support Oil State’s position. The argument involves the manner in which the Privy Council (and Queen’s) power to cancel was created for each patent by expressly including the power as an express caveat to each patent grant. In the US, these sorts of caveats were never included within the patent grant (as far as I’m aware), and certainly were not included within pre-AIA patents being cancelled via Inter Partes Review.

= = =

One further note for those delving into history: I mentioned Bracha’s Thesis work Owning Ideas: A History of Anglo-American Intellectual Property. Bracha has a much more recent book: Owning Ideas: The Intellectual Origins of American Intellectual Property, 1790–1909 (Cambridge Press 2016) that focuses on development of American law.