Gender Analytics: Using Litigation Data to Evaluate Law Firm Diversity

Patent – Patently-O 2017-09-06

Guest Post by By Michael Sander,[1] Tara Klamrowski, and Rachel Sander

Legal analytics can now identify law firms committed to gender diversity by analyzing the gender of attorney appearances. Docket Alarm has done so for the United States Supreme Court and specialized patent courts. The lack of gender diversity is significant, especially in patent cases. Here we highlight firms breaking the mold.

More women are entering the legal profession than ever —women now make up about half of all law students and 36% of all licensed attorneys— but these ratios are not reflected at the highest levels of firm positions. Judges anecdotally report that women rarely act as lead counsel in litigation, and the percentage of female partners at firms hovers around 22%.

Corporate clients are aware of the gender imbalance and actively seek out firms that reflect their own commitment to gender diversity. Clients now regularly request firm diversity statistics as part of law firm pitches, putting pressure on firms to support female attorneys at the highest ranks.

Law firms typically measure diversity by tracking headcount; the number of male and female associates and partners in their ranks. These metrics can ignore the often more meaningful metric of how often female attorneys actually appear in court-room litigation.

How Legal Analytics Can Help Quantify Firm Diversity

Modern legal analytics can play an important role in increasing transparency in law firm gender diversity. Traditional legal analytics show how often parties or law firms win cases, or the likelihood of winning legal relief in front of a particular judge. However, they can also be used to rank and analyze more general litigation trends, including gender diversity.

To identify firms with the most balanced male-female attorney ratio, Docket Alarm scours the litigation record, looking at the names of attorneys and their law firm. The gender of each attorney in a case is identified based on the attorney’s first name and other factors.[2]

The result is that we can now measure firm gender diversity based on attorneys actually staffed on cases, i.e., those that most substantively participate in litigation, not just by firm head-count.

Gender Analytics in the Patent Trial and Appeal Board AIA Trials

The analysis began with the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”), a specialized court focused on patent validity. The analysis shows that patent litigation is dominated by male attorneys. Of the top 100 law firms, 55 have less than 10% female attorneys on cases, and 8 firms have never had a single female attorney work on their PTAB AIA-Trial cases. On average, attorney appearances are only 12% female. When representing patent owners, the percentage of female attorneys drops further to 9.8%.

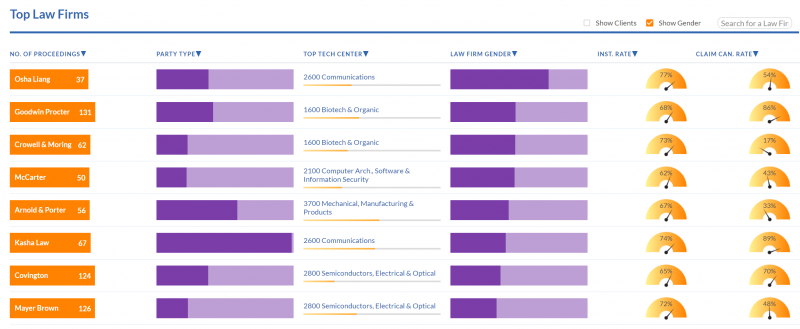

However, some firms buck the trend. According to Docket Alarm’s statistics, the firms with the highest ratios of female attorneys working on PTAB patent cases are as follows:

RankFirmPercentage Female1Osha Liang72%2Goodwin Proctor48%3Crowell & Moring47.3%4McCarter English46.7%5Arnold & Porter42%The “percentage female” here is calculated by dividing the number of female attorney appearances by the number of male and female attorney appearances for each firm.

Other runners up that have at least 25% of their AIA-Trial representations staffed by female attorneys include: Kasha Law; Covington & Burling; Mayer Brown; Drinker Biddle & Reath; Ascenda Law Group; Keker & Van Nest; Ropes & Gray; WilmerHale; and Venable.

The firms listed above, either by chance or design, have far more female attorneys working on cases than the average firm.

Fig. 1: Screenshot of Docket Alarm’s Gender Diversity Statistics in the PTAB

Gender Analytics in the U.S. Supreme Court

Compared to patent law, the male-female gap in Supreme Court practice is less severe, but by no means diverse. For the Supreme Court, Docket Alarm examined petitions for certiorari, analyzing the gender of the attorneys representing certiorari petitioners and respondents. Only two private law firms have half of their attorney appearances staffed by female attorneys, and only 7 have more than 25%. They are as follows:[3]

RankFirmPercentage Female1Dykema Gossett75%2Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan57%3Arnold & Porter35%4Morgan, Lewis & Bockius32.3%5Littler Mendelson32.2%6Latham & Watkins30.0%7Hogan Lovells29.9%In the rarefied world of Supreme Court practice, having just one or two top female attorneys on the team can make the firm a leader in gender diversity. Jill Wheaton leads Dykema’s Supreme Court practice. At Quinn Emanuel, it is Kathleen Sullivan and Sheila Birnbaum. Similarly, Deanne Maynard and Beth Brinkmann take the majority of cases at MoFo. These firms can attribute their strong diversity numbers to just a few highly specialized attorneys.

Win Rates and Gender Diversity

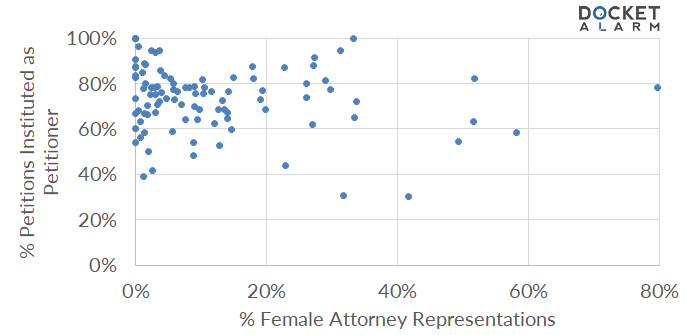

In addition to identifying the most gender diverse law firms, Docket Alarm’s analytics also show how case success rates are related to gender diverse firms. Docket Alarm found no statistically significant correlation between gender diversity and a firm’s win rate in the PTAB.[4]

Fig. 2: Petitioner Win Rates Plotted Against Gender Diversity in the PTAB

The Future of Diversity Analytics

Now that gender diversity is becoming part of the law firm sales pitch to clients, there is demand to identify firms committed to gender diversity, and for law firms to track diversity recruitment efforts.

Analytics can also identify gender diversity of a particular client’s legal team across law firms. This metric can help clients identify the progress of diversity efforts.

Analytics are leading the way for a new look at diversity in law, one that relies on actual client representation, and not just firm head-count. The initial statistics are not encouraging, especially in patent law, but they highlight firms that are making progress, and provide a baseline to measure future progress for everyone else.

= = = = =

[1] Michael Sander is the founder of Docket Alarm (https://www.docketalarm.com).

[2] Attorneys where the gender cannot be determined due to a gender-neutral first name are not included in the statistics so as to not skew the results one way or another.

[3] The analysis did not consider firms that made fewer than 30 appearances as either a petitioner or respondent in petitions for certiorari since 2000. In an effort to home in on private civil litigation, the analysis disregarded cases filed forma pauperis.

[4] The methodology used a bivariate linear regression model. From a sample of the most active 100 law firms, gender diversity (measured as a percentage of female attorneys at the firm) was regressed on both petition institution as well as claim cancelation. The analysis was run separately for firms representing petitioners and patent owners.