Patent Law at the Supreme Court December 2021

Patent – Patently-O 2021-12-14

by Dennis Crouch  The Supreme Court has not yet granted a writ of certiorari in any patent cases this term, and has denied certiorari in several dozen cases. A handful of important petitions are pending whose outcome could be transformative to the law.

The Supreme Court has not yet granted a writ of certiorari in any patent cases this term, and has denied certiorari in several dozen cases. A handful of important petitions are pending whose outcome could be transformative to the law.

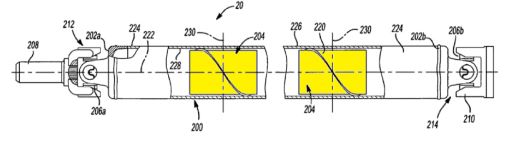

Eligibility: American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. v. Neapco Holdings LLC, No. 20-891. The Federal Circuit concluded that American Axle’s vehicle-manufacturing claims are ineligible under the two-part tests of Alice and Mayo. U.S. Patent No. 7,774,911 (Claim 22). The claims here are directed to a method of manufacturing an automobile drive-shaft with reduced vibration. The basic idea is to insert a liner into a hollow shaft. The liner though is special — it is made of a “reactive absorber” and its mass and stiffness have been “tuned” all for the purpose of attenuating both “shell mode vibrations” and “bending mode vibrations” of the shaft. The petition asks two questions:

- What does it mean to be “directed to” an ineligible concept? (Alice Step 1).

- Is eligibility a pure questions of law (based upon the claims); or is it a “question of fact for the jury based upon the state of the art at the time of the patent?”

The Federal Circuit released a first opinion in the case followed by a toned-down second opinion. Both opinions were opposed by Judge Moore who explained that even the second try was an “unprecedented expansion of § 101.” The en banc petition failed, but in a 6-6 tie. The petition includes several features making certiorari more likely: Issue of historic interest to the Supreme Court; Divided lower court; Multiple amici in support of hearing the case; Multiple similar petitions in other cases; and Prior statement from US Gov’t (Trump Admin) that the Post-Alice eligibility setup needs recalibration. The Court has also shown signs of interest, including an order for responsive briefing from Neapco, and a request for the views of the Solicitor General (CVSG). We are now awaiting those views, and I expect that the SG’s brief will give us the best clue as to the likely outcome. The Supreme Court requested briefing almost 8 months ago – on May 3, 2021. The five most recent CVSG briefs took an average of 5.5 months from the request to the brief. So, we’re at the extreme end of the scale for this one.

There are two other eligibility cases pending: Yanbin Yu, et al. v. Apple Inc., No. 21-811; and WhitServe LLC v. Dropbox, Inc., No. 21-812. Neither of these are likely to garner interest.

PTAB Practice: The Supreme Court has shown extensive interest in various aspects of AIA Trials. The top pending case in this area is Mylan v. Janssen. Mylan filed an IPR petition that was denied based upon the six-factor NHK-Fintiv Rule established under Dir. Iancu. NHK-Fintiv permits the PTAB to deny IPR institution in situations where a parallel district court litigation is already well under way. Mylan appealed the IPR institution denial, but the Federal Circuit dismissed for lack of appellate jurisdiction, citing 35 U.S.C. § 314(d) (“The determination by the Director whether to institute an inter partes review under this section shall be final and nonappealable.”).

In its petition, Mylan asks two questions:

- Does 35 U.S.C. § 314(d) categorically preclude appeal of all decisions not to institute inter partes review?

- Is the NHK-Fintiv Rule substantively and procedurally unlawful?

Mylan Laboratories Ltd. v. Janssen Pharmaceutica, N.V., No. 21-202. The petition has received amicus support as has a parallel petition in Apple Inc. v. Optis Cellular Technology, LLC, No. 21-118, asking whether the law permits either appeal or mandamus in situations where the PTO exceeds its authority in a way that “is arbitrary or capricious, or was adopted without required notice-and-comment rulemaking.”

More Appellate Standing: A third PTAB related appellate standing case is Apple Inc. v. Qualcomm Incorporated, No. 21-746, this one focusing on standing to appeal a final written decision. The patent act is clear that any “person” other than the patentee can file an IPR petition and, if granted, participate in the trial as a party. The statute goes on to indicate that “a party dissatisfied with the final written decision” has a right to appeal that decision to the Federal Circuit. 35 U.S.C. 319. Despite the statutory right to appeal, the Federal Circuit has still refused to hear appeals in situations where the appellant cannot show concrete injury caused by the PTAB decision and redressability of that injury. The appellate court’s grounding stems from the Constitutional requirement from Article III of an actual case or controversy.

Here, Apple licensed a large number of Qualcomm patents as part of a portfolio license, but has only challenged a couple of them via IPR. The PTAB sided with Qualcomm and Apple appealed. On appeal, the Federal Circuit found that Apple had not provided any immediate concrete injury associated with the patent’s existence and so dismissed the appeal. In particular, (1) the court was not shown how the license would change in any way if those patents fell-out; and (2) although the license was set to expire prior to the patents, the court found that potential infringement liability a few years now was too speculative. Apple has now petitioned for writ of certiorari with the following question: Whether a licensee has Article III standing to challenge the validity of a patent covered by a license agreement that covers multiple patents. As you can see, this question attempts to tie the case directly to MedImmune, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc., 549 U.S. 118 (2007) where the Supreme Court found standing for a licensee to challenge a patent.

Prior Art for IPRs: An interesting statutory interpretation petition was recently filed in Baxter Corporation Englewood v. Beckton, Dickinson and Company, No. 21-819. Congress was careful to limit the scope of IPR proceedings. The IPR petition may request claims “only on the basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.” 35 U.S.C. 314(b). In the case, expert testimony was used to fill a gap in the prior art, and the question is whether the use of expert testimony in this manner violates the statutory provision.

Full Scope Enablement: LDL (“bad cholesterol”) is removed by LDL receptors in the liver. That’s a good thing. But, the body also makes PCSK9, a protein that can bind to the LDL receptors and destroy them. Amgen’s solution is an antibody that competitively binds to PCSK9 in a way that prevents them from binding and harming the LDL receptors. The result then is lowering of LDL in the body.

A monoclonal antibody is a type of protein made up of amino acids. Amgen’s claims at issue here do not recite the particular amino acid sequence or how the protein is structured and chemically linked. Rather, the claims are directed to a whole genus of monoclonal antibodies defined by the ability to bind with PCSK9 in a way that blocks PCSK9 from also binding with the LDL receptor.

The jury sided with the patentee on the issue of enablement, but the district court rejected the verdict on renewed JMOL. On appeal, the Federal Circuit sided with the accused infringer — holding that enablement is a question of law, and that the claims were so broad that full-scope-enablement is virtually impossible. In its petition, Amgen argues that (1) enablement should be seen as a question of fact; and (2) that the law does not require “full scope enablement” to the extent demanded by the Federal Circuit here.

A Novel form of Preclusion, the Kessler Doctrine: Finally, we get to res judicata. Lawyers all learned about claim preclusion and issue preclusion. Those two principles of law are designed to ensure finality of judgment and avoid relitigation. History shows substantial confusion about both terminology and scope, but things have been substantially clear and steady since the adoption of the Restatement (Second) of Judgments in 1982. One aspect of the historic confusion stems from the Supreme Court’s 1907 decision of Kessler v. Eldred. Kessler has been on a back-burner for decades, but in 2014 the Federal Circuit revived the case and found that it deserved to co-equal — a preclusion doctrine separate and distinct from issue or claim preclusion. That 2014 Brain Life decision was followed by a further expansion of Kessler in Speedtrack (Fed. Cir. 2015) and again in PersonalWeb Techs. (2020).

PersonalWeb’s certiorari petition the Supreme Court asks two questions:

- Whether the Federal Circuit correctly interpreted Kessler to create a freestanding preclusion doctrine that [applies] even when claim and issue preclusion do not.

- Whether the Federal Circuit properly extended its Kessler doctrine to cases where the prior judgment was a voluntary dismissal.

The Supreme Court has shown interest in the case, and recently called for the Solicitor General to submit a brief on behalf of the U.S. Gov’t. I have an article on the case coming out in the Akron Law Review that I’ll post in a week or so (after fixing a few citations).

Two More: Although no petitions have been filed yet, the parties in two other cases have publicly indicated their intent to file petitions by the end of 2021:

- Intel Corporation v. VLSI Technology LLC (Follow-on case to Mylan v. Janssen and Apple v. Optis); and

- Ikorongo Texas LLC v. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. (proper venue in a situation where the plaintiff holds territorially limited patent right).

See you in January.