Definiteness: Federal Circuit’s Pliable Standard Results in Resilient Patent Claims

Patent – Patently-O 2022-04-11

by Dennis Crouch

Although Nautilus made it easier for a court to find claim terms indefinite, the Federal Circuit continues indicate that the definiteness test strongly favors validity.

In Niazi Licensing Corp. v. St. Jude Medical S.C., Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2022), the court has sided with the patentee–rejecting the district court’s indefiniteness finding.

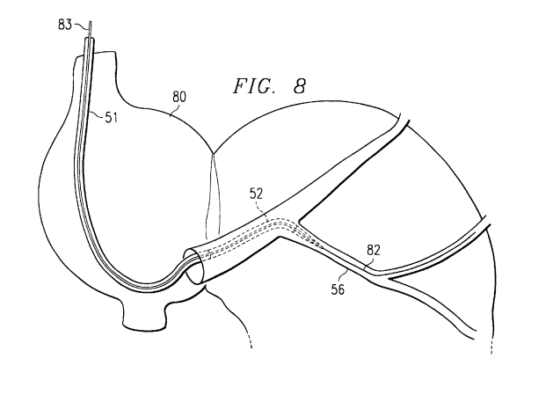

Niazi’s US6638268 covers a double lined catheter designed for placing an electrical lead in the coronary sinus vein. The outer catheter is a “resilient catheter having shape memory and a hook shaped distal end.” The inner catheter is a “pliable catheter.” In Figure 8 below, you can see that the larger outer catheter can get most of the way to the vein destination, but its less-pliable construction makes it difficult to follow all the twists. The pliable inner catheter is then inserted and extended to reach the vein location.

D.Minn. Judge Wright found the terms “resilient” and “pliable” indefinite and therefore that the claims were invalid. On appeal, the Federal Circuit has reversed–holding that terms meet the requirement of “reasonable certainty.” Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., 572 U.S. 898 (2014).

Patent law’s definiteness requirement is derived from the requirement that patent claims “particularly pointing out and distinctly claiming the subject matter” of the invention. 35 U.S.C. 112. The purpose of express claims is to provide public notice of the scope of exclusive rights so that competitors and potential copycats can arrange their affairs to avoid infringement. (We could pause here to question whether competitors and potential copycats do this in the ordinary course or if it is instead merely legal fiction.) But, the Supreme Court has also recognized that claims need not perfectly delineate claim scope — rather, the claims must provide “reasonable certainty” as to their scope. Nautilus. In particular, the Federal Circuit has repeatedly found terms of relative degree to be definite so long as POSITA would have “enough certainty.” Further, “a claim is not indefinite just because it is broad.” Slip Op. On the other hand, “purely subjective” claim terms are indefinite — such as “aesthetically pleasing” as used in Datamize, LLC v. Plumtree Software, Inc., 417 F.3d 1342, 1345, 1349–56 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (there must be some “objective anchor”).

Here, according to the court, Niazi’s claims terms provide enough guidance to avoid being labelled indefinite.

- Resilient: The claims require “an outer, resilient catheter having shape memory.” In its decision, the court concluded that resilient is guided by the “shape memory” requirement. The specification further explains that it may have a “braided design.” and may be made of “silastic or similar material” with the purpose of “return[ing] to its original shape” after being distorted. The specification also categories resilience in terms of both torque control and stiffness.

- Pliable: The claims require “an inner, pliable catheter slidably disposed in the outer catheter.” The specification provides further explanation: “constructed of a more pliable, soft material such as silicone;” and without “longitudinal braiding, which makes it extremely flexible and able to conform to various shapes.”

In addition to each having some amount of support from the specification, the court also noted that the two terms can be read relative to one another– the pliable inner catheter must be “more flexible than the outer.”

Definiteness is ordinarily a question of law and so the Federal Circuit reviews the issue de novo on appeal. Here, the court found sufficient reasons to find the terms definite. Reversed.

Note: The court also considered dictionary definitions. It did not discuss whether those definitions introduced extrinsic evidence requiring deference rather than de novo review.

= = = =

Niazi’s Claim 11 is a method-of-use claim that did not use the pliable/resilient terms. Thus, it survived the district court indefiniteness attack. The defendant here St. Jude supplied the accused catheter, and Niazi argued that St. Jude had induced doctors and hospitals to infringe. The district court found no inducement. On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed — holding that under the correct construction of the claim terms there was no underlying direct infringement.

= = = =

Exclusion as a Discovery Sanction: In his expert report, Dr. Niazi’s technical expert (Dr. Burke) stated that he had personally infringed the Niazi patent while using the accused products. The problem: Dr. Burke had not been identified as a fact witness as required by R.26(a)/(e). Dr. Niazi’s damages expert relied upon several license agreements to support his report. However, those agreements were not identified during fact discovery despite a specific request for documents. Both expert reports were provided after the close of fact discovery (as is common). As a sanction for the late disclosures, the District Court struck those facts from the expert reports and barred Dr. Burke from testifying as a factual witness. On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed on a technical ground — finding that Niazi’s appeal on this question failed because he did not challenge the actual basis for the district court’s decision–whether the delay in disclosure was “substantially justified or harmless.”

Despite the exclusion order, Niazi still presented a declaration from Dr. Burke in support of summary judgment that included a number of factual claims based upon Burke’s personal experience. The district court struck the statements and also awarded monetary sanctions under R. 37. The Federal Circuit affirmed:

Here, the sanctions the court imposed were specifically keyed to St. Jude’s expenses in moving to strike the already-excluded evidence from consideration at summary judgment. We see no abuse of discretion in the district court’s decision to award monetary sanctions.

Slip Op.

= = = =

Finally, the district court also excluded Niazi’s damage expert report as unreliable.

The district court excluded Mr. Carlson’s expert opinion as legally insufficient because Mr. Carlson failed to “apportion” between infringing and noninfringing uses and because he could not properly include leads in the royalty base. We affirm the district court’s exclusion.

Slip Op. Here, the idea was that St.Jude agued that some uses were non-infringing and the expert did not attempt to apportion-out the non-infringing uses but instead merely stated that apportionment would be “impractical in view of real-world considerations.”

Here, the claim was that sales by St. Jude (along with its instructions) were inducing infringement the method-of-use claims. The patentee argued that apportionment does not apply to method claims. But, the Federal Circuit disagreed with that broad statement. “Damages should be apportioned to separate out noninfringing uses, and patentees cannot recover damages based on sales of products with the mere capability to practice the claimed method. Rather, where the only asserted claim is a method claim, the damages base should be limited to products that were actually used to perform the claimed method.”