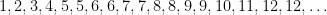

I have just uploaded to the arXiv my paper “Monotone non-decreasing sequences of the Euler totient function“. This paper concerns the quantity  , defined as the length of the longest subsequence of the numbers from

, defined as the length of the longest subsequence of the numbers from  to

to  for which the Euler totient function

for which the Euler totient function  is non-decreasing. The first few values of

is non-decreasing. The first few values of  are

are

(

OEIS A365339). For instance,

because the totient function is non-decreasing on the set

or

, but not on the set

.

Since  for any prime

for any prime  , we have

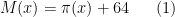

, we have  , where

, where  is the prime counting function. Empirically, the primes come quite close to achieving the maximum length

is the prime counting function. Empirically, the primes come quite close to achieving the maximum length  ; indeed it was conjectured by Pollack, Pomerance, and Treviño, based on numerical evidence, that one had

; indeed it was conjectured by Pollack, Pomerance, and Treviño, based on numerical evidence, that one had

for all

; this conjecture is verified up to

. The previous best known upper bound was basically of the form

as

for an explicit constant

, from combining results from the above paper with that

of Ford or

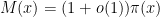

of Maier-Pomerance. In this paper we obtain the asymptotic

so in particular

. This answers a

question of Erdős, as well as a closely related question

of Pollack, Pomerance, and Treviño.

The methods of proof turn out to be mostly elementary (the most advanced result from analytic number theory we need is the prime number theorem with classical error term). The basic idea is to isolate one key prime factor  of a given number

of a given number  which has a sizeable influence on the totient function

which has a sizeable influence on the totient function  . For instance, for “typical” numbers

. For instance, for “typical” numbers  , one has a factorization

, one has a factorization

where

is a medium sized prime,

is a significantly larger prime, and

is a number with all prime factors less than

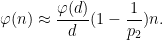

. This leads to an approximation

As a consequence, if we temporarily hold

fixed, and also localize

to a relatively short interval, then

can only be non-decreasing in

if

is also non-decreasing at the same time. This turns out to significantly cut down on the possible length of a non-decreasing sequence in this regime, particularly if

is large; this can be formalized by partitioning the range of

into various subintervals and inspecting how this (and the monotonicity hypothesis on

) constrains the values of

associated to each subinterval. When

is small, we instead use a factorization

where

is very smooth (i.e., has no large prime factors), and

is a large prime. Now we have the approximation

and we can conclude that

will have to basically be piecewise constant in order for

to be non-decreasing. Pursuing this analysis more carefully (in particular controlling the size of various exceptional sets in which the above analysis breaks down), we end up achieving the main theorem so long as we can prove the preliminary inequality

for all positive rational numbers

. This is in fact also a necessary condition; any failure of this inequality can be easily converted to a counterexample to the bound

(2), by considering numbers of the form

(3) with

equal to a fixed constant

(and omitting a few rare values of

where the approximation

(4) is bad enough that

is temporarily decreasing). Fortunately, there is a minor miracle, relating to the fact that the largest prime factor of denominator of

in lowest terms necessarily equals the largest prime factor of

, that allows one to evaluate the left-hand side of

(5) almost exactly (this expression either vanishes, or is the product of

for some primes

ranging up to the largest prime factor of

) that allows one to easily establish

(5). If one were to try to prove an analogue of our main result for the

sum-of-divisors function

, one would need the analogue

of

(5), which looks within reach of current methods (and was even claimed without proof

by Erdos), but does not have a full proof in the literature at present.

In the final section of the paper we discuss some near counterexamples to the strong conjecture (1) that indicate that it is likely going to be difficult to get close to proving this conjecture without assuming some rather strong hypotheses. Firstly, we show that failure of Legendre’s conjecture on the existence of a prime between any two consecutive squares can lead to a counterexample to (1). Secondly, we show that failure of the Dickson-Hardy-Littlewood conjecture can lead to a separate (and more dramatic) failure of (1), in which the primes are no longer the dominant sequence on which the totient function is non-decreasing, but rather the numbers which are a power of two times a prime become the dominant sequence. This suggests that any significant improvement to (2) would require assuming something comparable to the prime tuples conjecture, and perhaps also some unproven hypotheses on prime gaps.

, defined as the length of the longest subsequence of the numbers from

to

for which the Euler totient function

is non-decreasing. The first few values of

are

for any prime

, we have

, where

is the prime counting function. Empirically, the primes come quite close to achieving the maximum length

; indeed it was conjectured by Pollack, Pomerance, and Treviño, based on numerical evidence, that one had

of a given number

which has a sizeable influence on the totient function

. For instance, for “typical” numbers

, one has a factorization