A common task in analysis is to obtain bounds on sums

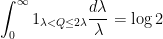

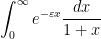

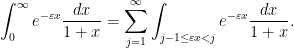

or integrals

where

is some simple region (such as an interval) in one or more dimensions, and

is an explicit (and

elementary) non-negative expression involving one or more variables (such as

or

, and possibly also some additional parameters. Often, one would be content with an order of magnitude upper bound such as

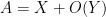

or

where we use

(or

or

) to denote the bound

for some constant

; sometimes one wishes to also obtain the matching lower bound, thus obtaining

or

where

is synonymous with

. Finally, one may wish to obtain a more precise bound, such as

where

is a quantity that goes to zero as the parameters of the problem go to infinity (or some other limit). (For a deeper dive into asymptotic notation in general, see

this previous blog post.)

Here are some typical examples of such estimation problems, drawn from recent questions on MathOverflow:

Compared to other estimation tasks, such as that of controlling oscillatory integrals, exponential sums, singular integrals, or expressions involving one or more unknown functions (that are only known to lie in some function spaces, such as an  space), high-dimensional geometry (or alternatively, large numbers of random variables), or number-theoretic structures (such as the primes), estimation of sums or integrals of non-negative elementary expressions is a relatively straightforward task, and can be accomplished by a variety of methods. The art of obtaining such estimates is typically not explicitly taught in textbooks, other than through some examples and exercises; it is typically picked up by analysts (or those working in adjacent areas, such as PDE, combinatorics, or theoretical computer science) as graduate students, while they work through their thesis or their first few papers in the subject.

space), high-dimensional geometry (or alternatively, large numbers of random variables), or number-theoretic structures (such as the primes), estimation of sums or integrals of non-negative elementary expressions is a relatively straightforward task, and can be accomplished by a variety of methods. The art of obtaining such estimates is typically not explicitly taught in textbooks, other than through some examples and exercises; it is typically picked up by analysts (or those working in adjacent areas, such as PDE, combinatorics, or theoretical computer science) as graduate students, while they work through their thesis or their first few papers in the subject.

Somewhat in the spirit of this previous post on analysis problem solving strategies, I am going to try here to collect some general principles and techniques that I have found useful for these sorts of problems. As with the previous post, I hope this will be something of a living document, and encourage others to add their own tips or suggestions in the comments.

— 1. Asymptotic arithmetic —

Asymptotic notation is designed so that many of the usual rules of algebra and inequality manipulation continue to hold, with the caveat that one has to be careful if subtraction or division is involved. For instance, if one knows that  and

and  , then one can immediately conclude that

, then one can immediately conclude that  and

and  , even if

, even if  are negative (note that the notation

are negative (note that the notation  or

or  automatically forces

automatically forces  to be non-negative). Equivalently, we have the rules

to be non-negative). Equivalently, we have the rules

and more generally we have the triangle inequality

(Again, we stress that this sort of rule implicitly requires the

to be non-negative. As a rule of thumb, if your calculations have arrived at a situation where a signed or oscillating sum or integral appears

inside the big-O notation, or on the right-hand side of an estimate, without being “protected” by absolute value signs, then you have probably made a serious error in your calculations.)

Another rule of inequalities that is inherited by asymptotic notation is that if one has two bounds

for the same quantity

, then one can combine them into the unified asymptotic bound

This is an example of a “free move”: a replacement of bounds that does not lose any of the strength of the original bounds, since of course

(2) implies

(1). In contrast, other ways to combine the two bounds

(1), such as taking the geometric mean

while often convenient, are not “free”: the bounds

(1) imply the averaged bound

(3), but the bound

(3) does not imply

(1). On the other hand, the inequality

(2), while it does not concede any logical strength, can require more calculation to work with, often because one ends up splitting up cases such as

and

in order to simplify the minimum. So in practice, when trying to establish an estimate, one often starts with using conservative bounds such as

(2) in order to maximize one’s chances of getting any proof (no matter how messy) of the desired estimate, and only after such a proof is found, one tries to look for more elegant approaches using less efficient bounds such as

(3).

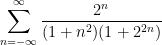

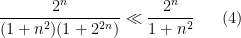

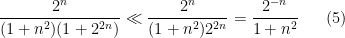

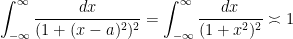

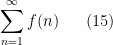

For instance, suppose one wanted to show that the sum

was convergent. Lower bounding the denominator term

by

or by

, one obtains the bounds

and also

so by applying

(2) we obtain the unified bound

To deal with this bound, we can split into the two contributions

, where

dominates, and

, where

dominates. In the former case we see (from the ratio test, for instance) that the sum

is absolutely convergent, and in the latter case we see that the sum

is also absolutely convergent, so the entire sum is absolutely convergent. But once one has this argument, one can try to streamline it, for instance by taking the geometric mean of

(4),

(5) rather than the minimum to obtain the weaker bound

and now one can conclude without decomposition just by observing the absolute convergence of the doubly infinite sum

. This is a less “efficient” estimate, because one has conceded a lot of the decay in the summand by using

(6) (the summand used to be exponentially decaying in

, but is now only polynomially decaying), but it is still sufficient for the purpose of establishing absolute convergence.

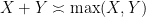

One of the key advantages of dealing with order of magnitude estimates, as opposed to sharp inequalities, is that the arithmetic becomes tropical. More explicitly, we have the important rule

whenver

are non-negative, since we clearly have

In praticular, if

, then

. That is to say, given two orders of magnitudes, any term

of equal or lower order to a “main term”

can be discarded. This is a very useful rule to keep in mind when trying to estimate sums or integrals, as it allows one to discard many terms that are not contributing to the final answer. It also sets up the fundamental

divide and conquer strategy for estimation: if one wants to prove a bound such as

, it will suffice to obtain a decomposition

or at least an upper bound

of

by some bounded number of components

, and establish the bounds

separately. Typically the

will be (morally at least) smaller than the original quantity

– for instance, if

is a sum of non-negative quantities, each of the

might be a subsum of those same quantities – which means that such a decomposition is a “free move”, in the sense that it does not risk making the problem harder. (This is because, if the original bound

is to be true, each of the new objectives

must also be true, and so the decomposition can only make the problem logically easier, not harder.) The only costs to such decomposition are that your proofs might be

times longer, as you may be repeating the same arguments

times, and that the implied constants in the

bounds may be worse than the implied constant in the original

bound. However, in many cases these costs are well worth the benefits of being able to simplify the problem into smaller pieces. As mentioned above, once one successfully executes a divide and conquer strategy, one can go back and try to reduce the number of decompositions, for instance by unifying components that are treated by similar methods, or by replacing strong but unwieldy estimates with weaker, but more convenient estimates.

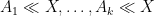

The above divide and conquer strategy does not directly apply when one is decomposing into an unbounded number of pieces  ,

,  . In such cases, one needs an additional gain in the index

. In such cases, one needs an additional gain in the index  that is summable in

that is summable in  in order to conclude. For instance, if one wants to establish a bound of the form

in order to conclude. For instance, if one wants to establish a bound of the form  , and one has located a decomposition or upper bound

, and one has located a decomposition or upper bound

that looks promising for the problem, then it would suffice to obtain exponentially decaying bounds such as

for all

and some constant

, since this would imply

thanks to the geometric series formula. (Here it is important that the implied constants in the asymptotic notation are uniform on

; a

-dependent bound such as

would be useless for this application, as then the growth of the implied constant in

could overwhelm the exponential decay in the

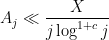

factor). Exponential decay is in fact overkill; polynomial decay such as

would already be sufficient, although harmonic decay such

is not quite enough (the sum

diverges logarithmically), although in many such situations one could try to still salvage the bound by working a lot harder to squeeze some additional logarithmic factors out of one’s estimates. For instance, if one can improve \eqre{ajx} to

for all

and some constant

, since (by the integral test) the sum

converges (and one can treat the

term separately if one already has

(8)).

Sometimes, when trying to prove an estimate such as  , one has identified a promising decomposition with an unbounded number of terms

, one has identified a promising decomposition with an unbounded number of terms

(where

is finite but unbounded) but is unsure of how to proceed next. Often the next thing to do is to study the extreme terms

and

of this decomposition, and first try to establish (the presumably simpler) tasks of showing that

and

. Often once one does so, it becomes clear how to combine the treatments of the two extreme cases to also treat the intermediate cases, obtaining a bound

for each individual term, leading to the inferior bound

; this can then be used as a starting point to hunt for additional gains, such as the exponential or polynomial gains mentioned previously, that could be used to remove this loss of

. (There are more advanced techniques, such as those based on controlling moments such as the square function

, or trying to understand the precise circumstances in which a “large values” scenario

occurs, and how these scenarios interact with each other for different

, but these are beyond the scope of this post, as they are rarely needed when dealing with sums or integrals of elementary functions.)

— 1.1. Psychological distinctions between exact and asymptotic arithmetic —

The adoption of the “divide and conquer” strategy requires a certain mental shift from the “simplify, simplify” strategy that one is taught in high school algebra. In the latter strategy, one tries to collect terms in an expression make them as short as possible, for instance by working with a common denominator, with the idea that unified and elegant-looking expressions are “simpler” than sprawling expressions with many terms. In contrast, the divide and conquer strategy is intentionally extremely willing to greatly increase the total length of the expressions to be estimated, so long as each individual component of the expressions appears easier to estimate than the original one. Both strategies are still trying to reduce the original problem to a simpler problem (or collection of simpler sub-problems), but the metric by which one judges whether the problem has become simpler is rather different.

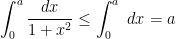

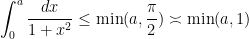

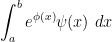

A related mental shift that one needs to adopt in analysis is to move away from the exact identities that are so prized in algebra (and in undergraduate calculus), as the precision they offer is often unnecessary and distracting for the task at hand, and often fail to generalize to more complicated contexts in which exact identities are no longer available. As a simple example, consider the task of estimating the expression

where

is a parameter. With a trigonometric substitution, one can evaluate this expression exactly as

, however the presence of the arctangent can be inconvenient if one has to do further estimation tasks (for instance, if

depends in a complicated fashion on other parameters, which one then also wants to sum or integrate over). Instead, by observing the trivial bounds

and

one can combine them using

(2) to obtain the upper bound

and similar arguments also give the matching lower bound, thus

This bound, while cruder than the exact answer of

, is often good enough for many applications (par ticularly in situations where one is willing to concede constants in the bounds), and can be more tractible to work with than the exact answer. Furthermore, these arguments can be adapted without difficulty to treat similar expressions such as

for any fixed exponent

, which need not have closed form exact expressions in terms of elementary functions such as the arctangent when

is non-integer.

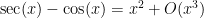

As a general rule, instead of relying exclusively on exact formulae, one should seek approximations that are valid up to the degree of precision that one seeks in the final estimate. For instance, suppose one one wishes to establish the bound

for all sufficiently small

. If one was clinging to the exact identity mindset, one could try to look for some trigonometric identity to simplify the left-hand side exactly, but the quicker (and more robust) way to proceed is just to use Taylor expansion up to the specified accuracy

to obtain

which one can invert using the geometric series formula

to obtain

from which the claim follows. (One could also have computed the Taylor expansion of

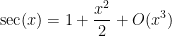

directly, but as this is a series that is usually not memorized, this can take a little bit more time than just computing it directly to the required accuracy.) Note that the notion of “specified accuracy” may have to be interpreted in a relative sense if one is planning to multiply or divide several estimates together. For instance, if one wishes to establsh the bound

for small

, one needs an approximation

to the sine function that is accurate to order

, but one only needs an approximation

to the cosine function that is accurate to order

, because the cosine is to be multiplied by

. Here the key is to obtain estimates that have a

relative error of

, compared to the main term (which is

for cosine, and

for sine).

The following table lists some common approximations that can be used to simplify expressions when one is only interested in order of magnitude bounds (with  an arbitrary small constant):

an arbitrary small constant):

The quantity… is comparable to … provided that…

or

,

,

real

real

,

,

,

real

,

,

,

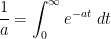

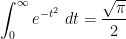

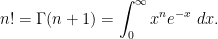

On the other hand, some exact formulae are still very useful, particularly if the end result of that formula is clean and tractable to work with (as opposed to involving somewhat exotic functions such as the arctangent). The geometric series formula, for instance, is an extremely handy exact formula, so much so that it is often desirable to control summands by a geometric series purely to use this formula (we already saw an example of this in (7)). Exact integral identities, such as

or more generally

for

(where

is the

Gamma function) are also quite commonly used, and fundamental exact integration rules such as the change of variables formula, the Fubini-Tonelli theorem or integration by parts are all esssential tools for an analyst trying to prove estimates. Because of this, it is often desirable to estimate a sum by an integral. The

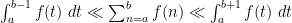

integral test is a classic example of this principle in action: a more quantitative versions of this test is the bound

whenever

are integers and

![{f: [a-1,b+1] \rightarrow {\bf R}}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7Bf%3A+%5Ba-1%2Cb%2B1%5D+%5Crightarrow+%7B%5Cbf+R%7D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002)

is monotone decreasing, or the closely related bound

whenever

are reals and

![{f: [a,b] \rightarrow {\bf R}}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7Bf%3A+%5Ba%2Cb%5D+%5Crightarrow+%7B%5Cbf+R%7D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002)

is monotone (either increasing or decreasing); see Lemma 2 of

this previous post. Such bounds allow one to switch back and forth quite easily between sums and integrals as long as the summand or integrand behaves in a mostly monotone fashion (for instance, if it is monotone increasing on one portion of the domain and monotone decreasing on the other). For more precision, one could turn to more advanced relationships between sums and integrals, such as the

Euler-Maclaurin formula or the

Poisson summation formula, but these are beyond the scope of this post.

Exercise 1 Suppose  obeys the quasi-monotonicity property

obeys the quasi-monotonicity property  whenever

whenever  . Show that

. Show that  for any integers

for any integers  .

.

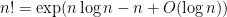

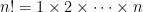

Exercise 2 Use (11) to obtain the “cheap Stirling approximation”

for any natural number  . (Hint: take logarithms to convert the product

. (Hint: take logarithms to convert the product  into a sum.)

into a sum.)

With practice, you will be able to identify any term in a computation which is already “negligible” or “acceptable” in the sense that its contribution is always going to lead to an error that is smaller than the desired accuracy of the final estimate. One can then work “modulo” these negligible terms and discard them as soon as they appear. This can help remove a lot of clutter in one’s arguments. For instance, if one wishes to establish an asymptotic of the form

for some main term

and lower order error

, any component of

that one can already identify to be of size

is negligible and can be removed from

“for free”. Conversely, it can be useful to

add negligible terms to an expression, if it makes the expression easier to work with. For instance, suppose one wants to estimate the expression

This is a partial sum for the zeta function

so it can make sense to add and subtract the tail

to the expression

(12) to rewrite it as

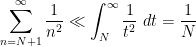

To deal with the tail, we switch from a sum to the integral using

(10) to bound

giving us the reasonably accurate bound

One can sharpen this approximation somewhat using

(11) or the Euler–Maclaurin formula; we leave this to the interested reader.

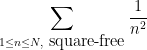

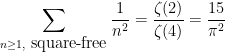

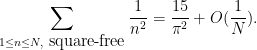

Another psychological shift when switching from algebraic simplification problems to estimation problems is that one has to be prepared to let go of constraints in an expression that complicate the analysis. Suppose for instance we now wish to estimate the variant

of

(12), where we are now restricting

to be

square-free. An identity from analytic number theory (the

Euler product identity) lets us calculate the exact sum

so as before we can write the desired expression as

Previously, we applied the integral test

(10), but this time we cannot do so, because the restriction to square-free integers destroys the monotonicity. But we can simply remove this restriction:

Heuristically at least, this move only “costs us a constant”, since a positive fraction (

, in fact) of all integers are square-free. Now that this constraint has been removed, we can use the integral test as before and obtain the reasonably accurate asymptotic

— 2. More on decomposition —

The way in which one decomposes a sum or integral such as  or

or  is often guided by the “geometry” of

is often guided by the “geometry” of  , and in particular where

, and in particular where  is large or small (or whether various component terms in

is large or small (or whether various component terms in  are large or small relative to each other). For instance, if

are large or small relative to each other). For instance, if  comes close to a maximum at some point

comes close to a maximum at some point  , then it may make sense to decompose based on the distance

, then it may make sense to decompose based on the distance  to

to  , or perhaps to treat the cases

, or perhaps to treat the cases  and

and  separately. (Note that

separately. (Note that  does not literally have to be the maximum in order for this to be a reasonable decomposition; if it is in “within reasonable distance” of the maximum, this could still be a good move. As such, it is often not worthwhile to try to compute the maximum of

does not literally have to be the maximum in order for this to be a reasonable decomposition; if it is in “within reasonable distance” of the maximum, this could still be a good move. As such, it is often not worthwhile to try to compute the maximum of  exactly, especially if this exact formula ends up being too complicated to be useful.)

exactly, especially if this exact formula ends up being too complicated to be useful.)

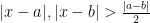

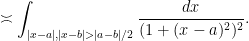

If an expression involves a distance  between two quantities

between two quantities  , it is sometimes useful to split into the case

, it is sometimes useful to split into the case  where

where  is much smaller than

is much smaller than  (so that

(so that  ), the case

), the case  where

where  is much smaller than

is much smaller than  (so that

(so that  ), or the case when neither of the two previous cases apply (so that

), or the case when neither of the two previous cases apply (so that  ). The factors of

). The factors of  here are not of critical importance; the point is that in each of these three cases, one has some hope of simplifying the expression into something more tractable. For instance, suppose one wants to estimate the expression

here are not of critical importance; the point is that in each of these three cases, one has some hope of simplifying the expression into something more tractable. For instance, suppose one wants to estimate the expression

in terms of the two real parameters

, which we will take to be distinct for sake of this discussion. This particular integral is simple enough that it can be evaluated exactly (for instance using contour integration techniques), but in the spirit of Principle 1, let us avoid doing so and instead try to decompose this expression into simpler pieces. A graph of the integrand reveals that it peaks when

is near

or near

. Inspired by this, one can decompose the region of integration into three pieces:

- (i) The region where

.

.

- (ii) The region where

.

.

- (iii) The region where

.

.

(This is not the only way to cut up the integral, but it will suffice. Often there is no “canonical” or “elegant” way to perform the decomposition; one should just try to find a decomposition that is convenient for the problem at hand.)

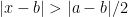

The reason why we want to perform such a decomposition is that in each of the three cases, one can simplify how the integrand depends on  . For instance, in region (i), we see from the triangle inequality that

. For instance, in region (i), we see from the triangle inequality that  is now comparable to

is now comparable to  , so that this contribution to (13) is comparable to

, so that this contribution to (13) is comparable to

Using a variant of

(9), this expression is comparable to

The contribution of region (ii) can be handled similarly, and is also comparable to

(14). Finally, in region (iii), we see from the triangle inequality that

are now comparable to each other, and so the contribution of this region is comparable to

Now that we have centered the integral around

, we will discard the

constraint, upper bounding this integral by

On the one hand this integral is bounded by

and on the other hand we can bound

and so we can bound the contribution of (iii) by

. Putting all this together, and dividing into the cases

and

, one can soon obtain a total bound of

for the entire integral. One can also adapt this argument to show that this bound is sharp up to constants, thus

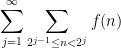

A powerful and common type of decomposition is dyadic decomposition. If the summand or integrand involves some quantity  in a key way, it is often useful to break up into dyadic regions such as

in a key way, it is often useful to break up into dyadic regions such as  , so that

, so that  , and then sum over

, and then sum over  . (One can tweak the dyadic range

. (One can tweak the dyadic range  here with minor variants such as

here with minor variants such as  , or replace the base

, or replace the base  by some other base, but these modifications mostly have a minor aesthetic impact on the arguments at best.) For instance, one could break up a sum

by some other base, but these modifications mostly have a minor aesthetic impact on the arguments at best.) For instance, one could break up a sum

into dyadic pieces

and then seek to estimate each dyadic block

separately (hoping to get some exponential or polynomial decay in

). The classical technique of

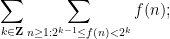

Cauchy condensation is a basic example of this strategy. But one can also dyadically decompose other quantities than

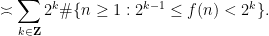

. For instance one can perform a “vertical” dyadic decomposition (in contrast to the “horizontal” one just performed) by rewriting

(15) as

since the summand

is

, we may simplify this to

This now converts the problem of estimating the sum

(15) to the more combinatorial problem of estimating the size of the dyadic level sets

for various

. In a similar spirit, we have

where

denotes the Lebesgue measure of a set

, and now we are faced with a geometric problem of estimating the measure of some explicit set. This allows one to use geometric intuition to solve the problem, instead of multivariable calculus:

Exercise 3 Let  be a smooth compact submanifold of

be a smooth compact submanifold of  . Establish the bound

. Establish the bound

for all  , where the implied constants are allowed to depend on

, where the implied constants are allowed to depend on  . (This can be accomplished either by a vertical dyadic decomposition, or a dyadic decomposition of the quantity

. (This can be accomplished either by a vertical dyadic decomposition, or a dyadic decomposition of the quantity  .)

.)

Exercise 4 Solve problem (ii) from the introduction to this post by dyadically decomposing in the  variable.

variable.

Remark 5 By such tools as (10), (11), or Exercise 1, one could convert the dyadic sums one obtains from dyadic decomposition into integral variants. However, if one wished, one could “cut out the middle-man” and work with continuous dyadic decompositions rather than discrete ones. Indeed, from the integral identity

for any  , together with the Fubini–Tonelli theorem, we obtain the continuous dyadic decomposition

, together with the Fubini–Tonelli theorem, we obtain the continuous dyadic decomposition

for any quantity  that is positive whenever

that is positive whenever  is positive. Similarly if we work with integrals

is positive. Similarly if we work with integrals  rather than sums. This version of dyadic decomposition is occasionally a little more convenient to work with, particularly if one then wants to perform various changes of variables in the

rather than sums. This version of dyadic decomposition is occasionally a little more convenient to work with, particularly if one then wants to perform various changes of variables in the  parameter which would be tricky to execute if this were a discrete variable.

parameter which would be tricky to execute if this were a discrete variable.

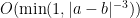

— 3. Exponential weights —

Many sums involve expressions that are “exponentially large” or “exponentially small” in some parameter. A basic rule of thumb is that any quantity that is “exponentially small” will likely give a negligible contribution when compared against quantities that are not exponentially small. For instance, if an expression involves a term of the form  for some non-negative quantity

for some non-negative quantity  , which can be bounded on at least one portion of the domain of summation or integration, then one expects the region where

, which can be bounded on at least one portion of the domain of summation or integration, then one expects the region where  is bounded to provide the dominant contribution. For instance, if one wishes to estimate the integral

is bounded to provide the dominant contribution. For instance, if one wishes to estimate the integral

for some

, this heuristic suggests that the dominant contribution should come from the region

, in which one can bound

simply by

and obtain an upper bound of

To make such a heuristic precise, one can perform a dyadic decomposition in the exponential weight  , or equivalently perform an additive decomposition in the exponent

, or equivalently perform an additive decomposition in the exponent  , for instance writing

, for instance writing

Exercise 6 Use this decomposition to rigorously establish the bound

for any  .

.

Exercise 7 Solve problem (i) from the introduction to this post.

More generally, if one is working with a sum or integral such as

or

with some exponential weight

and a lower order amplitude

, then one typically expects the dominant contribution to come from the region where

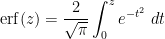

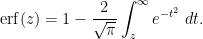

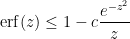

comes close to attaining its maximal value. If this maximum is attained on the boundary, then one typically has geometric series behavior away from the boundary, and one can often get a good estimate by obtaining geometric series type behavior. For instance, suppose one wants to estimate the error function

for

. In view of the complete integral

we can rewrite this as

The exponential weight

attains its maximum at the left endpoint

and decays quickly away from that endpoint. One could estimate this by dyadic decomposition of

as discussed previously, but a slicker way to proceed here is to use the convexity of

to obtain a geometric series upper bound

for

, which on integration gives

giving the asymptotic

for

.

Exercise 8 In the converse direction, establish the upper bound

for some absolute constant  and all

and all  .

.

Exercise 9 If  for some

for some  , show that

, show that

(Hint: estimate the ratio between consecutive binomial coefficients  and then control the sum by a geometric series).

and then control the sum by a geometric series).

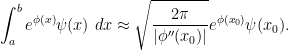

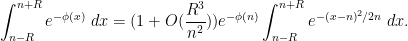

When the maximum of the exponent  occurs in the interior of the region of summation or integration, then one can get good results by some version of <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laplace

occurs in the interior of the region of summation or integration, then one can get good results by some version of <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laplace

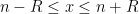

where

attains a non-degenerate global maximum at some interior point

. The rule of thumb here is that

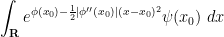

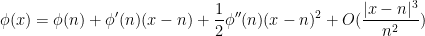

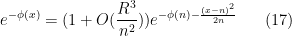

The heuristic justification is as follows. The main contribution should be when

is close to

. Here we can perform a Taylor expansion

since at a non-degenerate maximum we have

and

. Also, if

is continuous, then

when

is close to

. Thus we should be able to estimate the above integral by the gaussian integral

which can be computed to equal

as desired.

Let us illustrate how this argument can be made rigorous by considering the task of estimating the factorial  of a large number. In contrast to what we did in Exercise \ref”>, we will proceed using a version of Laplace’s method, relying on the integral representation

of a large number. In contrast to what we did in Exercise \ref”>, we will proceed using a version of Laplace’s method, relying on the integral representation

As

is large, we will consider

to be part of the exponential weight rather than the amplitude, writing this expression as

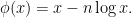

where

The function

attains a global maximum at

, with

and

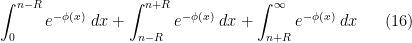

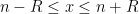

. We will therefore decompose this integral into three pieces

where

is a radius parameter which we will choose later, as it is not immediately obvious for now how to select it.

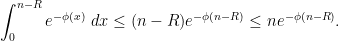

The main term is expected to be the middle term, so we shall use crude methods to bound the other two terms. For the first part where  ,

,  is increasing so we can crudely bound

is increasing so we can crudely bound  and thus

and thus

(We expect

to be much smaller than

, so there is not much point to saving the tiny

term in the

factor.) For the third part where

,

is decreasing, but bounding

by

would not work because of the unbounded nature of

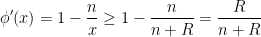

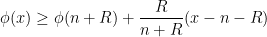

; some additional decay is needed. Fortunately, we have a strict increase

for

, so by the intermediate value theorem we have

and after a short calculation this gives

Now we turn to the important middle term. If we assume

, then we will have

in the region

, so by Taylor’s theorem with remainder

If we assume that

, then the error term is bounded and we can exponentiate to obtain

for

and hence

If we also assume that

, we can use the error function type estimates from before to estimate

Putting all this together, and using \eqref for details.

Exercise 10 Solve problem (iii) from the introduction. (Hint: extract out the term  to write as the exponential factor

to write as the exponential factor  , placing all the other terms (which are of polynomial size) in the amplitude function

, placing all the other terms (which are of polynomial size) in the amplitude function  . The function

. The function  will then attain a maximum at

will then attain a maximum at  ; perform a Taylor expansion and mimic the arguments above.)

; perform a Taylor expansion and mimic the arguments above.)

and

, is the expression

, how can one show that

for an explicit constant

, and what is this constant?

space), high-dimensional geometry (or alternatively, large numbers of random variables), or number-theoretic structures (such as the primes), estimation of sums or integrals of non-negative elementary expressions is a relatively straightforward task, and can be accomplished by a variety of methods. The art of obtaining such estimates is typically not explicitly taught in textbooks, other than through some examples and exercises; it is typically picked up by analysts (or those working in adjacent areas, such as PDE, combinatorics, or theoretical computer science) as graduate students, while they work through their thesis or their first few papers in the subject.

and

, then one can immediately conclude that

and

, even if

are negative (note that the notation

or

automatically forces

to be non-negative). Equivalently, we have the rules

,

. In such cases, one needs an additional gain in the index

that is summable in

in order to conclude. For instance, if one wants to establish a bound of the form

, and one has located a decomposition or upper bound

, one has identified a promising decomposition with an unbounded number of terms

an arbitrary small constant):

obeys the quasi-monotonicity property

whenever

. Show that

for any integers

.

. (Hint: take logarithms to convert the product

into a sum.)

or

is often guided by the “geometry” of

, and in particular where

is large or small (or whether various component terms in

are large or small relative to each other). For instance, if

comes close to a maximum at some point

, then it may make sense to decompose based on the distance

to

, or perhaps to treat the cases

and

separately. (Note that

does not literally have to be the maximum in order for this to be a reasonable decomposition; if it is in “within reasonable distance” of the maximum, this could still be a good move. As such, it is often not worthwhile to try to compute the maximum of

exactly, especially if this exact formula ends up being too complicated to be useful.)

between two quantities

, it is sometimes useful to split into the case

where

is much smaller than

(so that

), the case

where

is much smaller than

(so that

), or the case when neither of the two previous cases apply (so that

). The factors of

here are not of critical importance; the point is that in each of these three cases, one has some hope of simplifying the expression into something more tractable. For instance, suppose one wants to estimate the expression

.

.

.

. For instance, in region (i), we see from the triangle inequality that

is now comparable to

, so that this contribution to (13) is comparable to

in a key way, it is often useful to break up into dyadic regions such as

, so that

, and then sum over

. (One can tweak the dyadic range

here with minor variants such as

, or replace the base

by some other base, but these modifications mostly have a minor aesthetic impact on the arguments at best.) For instance, one could break up a sum

be a smooth compact submanifold of

. Establish the bound

, where the implied constants are allowed to depend on

. (This can be accomplished either by a vertical dyadic decomposition, or a dyadic decomposition of the quantity

.)

variable.

, together with the Fubini–Tonelli theorem, we obtain the continuous dyadic decomposition

that is positive whenever

is positive. Similarly if we work with integrals

rather than sums. This version of dyadic decomposition is occasionally a little more convenient to work with, particularly if one then wants to perform various changes of variables in the

parameter which would be tricky to execute if this were a discrete variable.

for some non-negative quantity

, which can be bounded on at least one portion of the domain of summation or integration, then one expects the region where

is bounded to provide the dominant contribution. For instance, if one wishes to estimate the integral

, or equivalently perform an additive decomposition in the exponent

, for instance writing

.

and all

.

for some

, show that

and then control the sum by a geometric series).

occurs in the interior of the region of summation or integration, then one can get good results by some version of <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laplace

of a large number. In contrast to what we did in Exercise \ref”>, we will proceed using a version of Laplace’s method, relying on the integral representation

,

is increasing so we can crudely bound

and thus

to write as the exponential factor

, placing all the other terms (which are of polynomial size) in the amplitude function

. The function

will then attain a maximum at

; perform a Taylor expansion and mimic the arguments above.)