I have just uploaded to the arXiv my paper “A Maclaurin type inequality“. This paper concerns a variant of the Maclaurin inequality for the elementary symmetric means

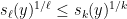

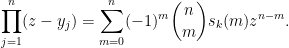

of

real numbers

. This inequality asserts that

whenever

and

are non-negative. It can be proven as a consequence of the

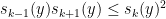

Newton inequality

valid for all

and arbitrary real

(in particular, here the

are allowed to be negative). Note that the

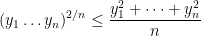

case of this inequality is just the arithmetic mean-geometric mean inequality

the general case of this inequality can be deduced from this special case by a number of standard manipulations (the most non-obvious of which is the operation of differentiating the real-rooted polynomial

to obtain another real-rooted polynomial, thanks to

Rolle’s theorem; the key point is that this operation preserves all the elementary symmetric means up to

). One can think of Maclaurin’s inequality as providing a refined version of the arithmetic mean-geometric mean inequality on

variables (which corresponds to the case

,

).

Whereas Newton’s inequality works for arbitrary real  , the Maclaurin inequality breaks down once one or more of the

, the Maclaurin inequality breaks down once one or more of the  are permitted to be negative. A key example occurs when

are permitted to be negative. A key example occurs when  is even, half of the

is even, half of the  are equal to

are equal to  , and half are equal to

, and half are equal to  . Here, one can verify that the elementary symmetric means

. Here, one can verify that the elementary symmetric means  vanish for odd

vanish for odd  and are equal to

and are equal to  for even

for even  . In particular, some routine estimation then gives the order of magnitude bound

. In particular, some routine estimation then gives the order of magnitude bound

for

even, thus giving a significant violation of the Maclaurin inequality even after putting absolute values around the

. In particular, vanishing of one

does not imply vanishing of all subsequent

.

On the other hand, it was observed by Gopalan and Yehudayoff that if two consecutive values  are small, then this makes all subsequent values

are small, then this makes all subsequent values  small as well. More precise versions of this statement were subsequently observed by Meka-Reingold-Tal and <a href="https://zbmath.org/?q=rf

small as well. More precise versions of this statement were subsequently observed by Meka-Reingold-Tal and <a href="https://zbmath.org/?q=rf

whenever

and

are real (but possibly negative). For instance, setting

we obtain the inequality

which can be established by combining the arithmetic mean-geometric mean inequality

with the \href”>

As with the proof of the Newton inequalities, the general case of

(2) can be obtained from this special case after some standard manipulations (including the differentiation operation mentioned previously).

However, if one inspects the bound (2) against the bounds (1) given by the key example, we see a mismatch – the right-hand side of (2) is larger than the left-hand side by a factor of about  . The main result of the paper rectifies this by establishing the optimal (up to constants) improvement

. The main result of the paper rectifies this by establishing the optimal (up to constants) improvement

of

(2). This answers a question

posed on MathOverflow.

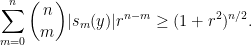

Unlike the previous arguments, we do not rely primarily on the arithmetic mean-geometric mean inequality. Instead, our primary tool is a new inequality

valid for all

and

. Roughly speaking, the bound

(3) would follow from

(4) by setting

, provided that we can show that the

terms of the left-hand side dominate the sum in this regime. This can be done, after a technical step of passing to tuples

which nearly optimize the required inequality

(3).

We sketch the proof of the inequality (4) as follows. One can use some standard manipulations reduce to the case where  and

and  , and after replacing

, and after replacing  with

with  one is now left with establishing the inequality

one is now left with establishing the inequality

Note that equality is attained in the previously discussed example with half of the

equal to

and the other half equal to

, thanks to the binomial theorem.

To prove this identity, we consider the polynomial

Evaluating this polynomial at

, taking absolute values, using the triangle inequality, and then taking logarithms, we conclude that

A convexity argument gives the lower bound

while the normalization

gives

and the claim follows.

, the Maclaurin inequality breaks down once one or more of the

are permitted to be negative. A key example occurs when

is even, half of the

are equal to

, and half are equal to

. Here, one can verify that the elementary symmetric means

vanish for odd

and are equal to

for even

. In particular, some routine estimation then gives the order of magnitude bound

are small, then this makes all subsequent values

small as well. More precise versions of this statement were subsequently observed by Meka-Reingold-Tal and <a href="https://zbmath.org/?q=rf

. The main result of the paper rectifies this by establishing the optimal (up to constants) improvement

and

, and after replacing

with

one is now left with establishing the inequality