The road closure property

Peter Cameron's Blog 2022-12-21

My work with João Araújo and other semigroup theorists has produced a number of permutation group properties which lie between primitivity and 2-homogeneity, especially the synchronization family. Another of these is the road closure propery, which I have discussed here before. Last week, we had a workshop to try to understand this property.

The workshop was in the Convento do Arrábida, an old Franciscan monastery in a national park on the side of a mountain overlooking the sea, just south of Lisbon (on the tongue of land which ends at Cabo Espichel). A beautiful spot, although for the first three days of the workshop there was fog, rain and strong wind, so we had to wait for the stunning views. There was nothing to do but work, and work we did.

Let G be a permutation group on Ω. The orbital graphs for G are the graphs on the vertex set Ω whose edges are the orbits of G on 2-element subsets of Ω, thus one graph for each orbit. A permutation group is transitive if it fixes no subset of Ω except for Ω and the empty set, and is primitive if in addition it fixes no partition of Ω except the partition into singletons and the partition with a single part. According to a theorem of Donald Higman, G is primitive if and only if all its orbital graphs are connected. G is 2-homogeneous if it has just a single orbit on the 2-element subsets of Ω, that is, it has just one orbital graph which is the complete graph. So a 2-homogeneous group is primitive.

We say that G has the road closure property if, for any orbit O of G on 2-sets, and any proper block of imprimitivity B for the action of G on O, the graph with edge set O\B is connected. That is, if an orbital graph for G represents a road network, and if the roads in a block B are all closed for roadworks, it is still possible to travel around the network. It is clear that the road closure property implies primitivity. Also, the complete graph (on more than two vertices) cannot be disconnected by removing a block, since if it could then it would be the union of two disconnected graphs; so a 2-homogeneous group has the road closure property.

Why would anyone invent such a strange property? It turns out that it is motivated by semigroup theory. One very important class of semigroups consists of the idempotent-generated semigroups (an idempotent is an element equal to its square). Now we consider semigroups obtained by adding a non-permutation f to the group G and generating a semigroup ⟨G,f⟩, then removing the elements of G (since the only permutation which is an idempotent is the identity). We look for properties such as idempotent-generation for this semigroup, call it S (depending on G and f). Understanding such semigroups is the first step towards understanding all transformation semigroups having G as group of units, or normalizer.

Now it can be shown, fairly easily, that for a given group G,

S contains an idempotent for any choice of f of rank 2 if and only if G is primitive.

Furthermore, with a rather longer proof,

S is idempotent-generated for any choice of f of rank 2 if and only if G has the road closure property.

(The rank of a transformation is the size of its image.)

The gap between primitivity and the road closure property is not large; most primitive groups have the RCP (as I will call it). One example where it fails is provided by the non-basic groups. A primitive group G is non-basic if it is contained in a wreath product Sq wr Sm in its product action of degree qm. This can be said another way. The Hamming graph H(m,q) has as vertices the set of all words of length m over an alphabet of size q; two vertices are adjacent if the words differ in exactly one coordinate (in coding theory terms, they have Hamming distance 1). Now the automorphism group of the Hamming graph is the wreath product of symmetric groups mentioned above; so G is non-basic if it acts as a group of automorphisms of a Hamming graph. Now, in the Hamming graph, each edge has a direction, the number of the coordinate in which their vertices differ; the set of edges with a given direction is a block of imprimitivity, and if we remove the ith block, then we can no longer change the ith coordinate by moving along the remaining edges, so the graph is disconnected.

Now a primitive group G is basic if it is not non-basic; and the task of the road closure problem is to describe all basic primitive groups which fail to have the road closure property.

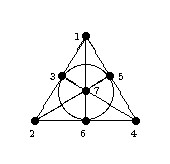

Here is an example, which ties in with our deliberations in Arrábida. Consider our old friend the Fano plane.

Let G be the group of collineations and correlations (dualities) of this plane; this is a group of order 336 isomorphic to PGL(2,7). There are two primitive actions of G, on the 21 flags (the incident point-line pairs) and on the 28 antiflags (the non-incident point-line pairs). Both actions are basic (since their degrees are not proper powers); both fail the road closure property. This can be seen by similar arguments in each case, but there is a simple way to see both.

The orbital graphs are constructed similarly: the vertices are the flags (or antiflags); two vertices are joined if they share either a point or a line. Now construct a 7×7 array whose columns are indexed by the points and rows by the lines. Then G acts on this array with two orbits, the flags and the antiflags. Now it is easy to see that that, in each orbital graph, the horizontal and vertical edges form blocks of imprimitivity; and, just as in the non-basic case, removing a block disconnects both graphs.

According to the O’Nan–Scott Theorem, basic primitive groups are of one of three types: affine, diagonal and almost simple. Pablo Spiga, one of the participants in the workshop, has a proof that all basic affine groups have the RCP. We expect the same for diagonal groups. The problem, then, should reduce to considering almost simple groups, of which PGL(2,7) gives the smallest two examples.

A program written by Leonard Soicher, another participant, examined primitive groups of degree up to 4095 (the limit of the GAP library) and found that, in all cases where the stabilizer of a block contains the socle, there are just two blocks, as in this example. But we do have examples with three blocks. I mentioned one in the previous post; Pablo has another, of degree 6000, which may well be the smallest such. We have no examples with more than three blocks.

So a reasonable goal for the road closure program would be to show that there cannot be more than three blocks, and perhaps to classify the groups which have three blocks.

We cannot yet do that. But we have shown that, apart from cases where the block stabiliser contains the socle of the group, there are two other possibilities:

- G is the symmetric or alternating group of degree m (the number of blocks), and the given action is of rather large degree (at least 2m);

- Ω can be identified with a subset of the set of k-element subsets of {1,…,m}, and adjacent pairs of subsets meet in a constant number of points.

No examples are known for any of these cases, and we have further numerical information which hopefully will allow us to elimiate them.

But there was more.

As described above, the RCP is equivalent to the statement that, for every rank 2 map f, the semigroup S obtained by generating a semigroup with G and f and then removing G is idempotent generated. So the alternative name for the RCP is the 2-idempotent generated property, or 2-id for short. But of course we can define k-id for any k≥2, and ask for a list of such groups.

The first major step has already been taken. A permutation group G has the k-universal transversal property, or k-ut for short, if given any k-subset A and k-partition P of Ω, there is an element g of the group G which maps A to a transversal to P. This property is equivalent to the statement that the semigroup S contains an idempotent, and so is weaker than k-id. Now we have previously studied groups with k-ut; they are all known apart from some families and some sporadic groups where we have been unable to decide. So the problem is to investigate these groups and determine which (out of those which definitely or possibly have k-ut) have k-id. At the workshop, João Araújo and Wolfram Bentz made some significant progress on this question.

I should add here that, for the case of 2-id groups, we have a combinatorial property involving objects of size polynomial in n which is equivalent, namely the RCP. This is lacking for higher values of k, and it is difficult for someone like me to understand exactly what makes the semigroup S idempotent-generated. Fortunately, negative results can be obtained by making a good guess about the k-partition to test, without needing to test them all.

In conclusion, we had a week in a stunningly beautiful place. The food was absolutely outstanding; Portuguese cuisine at its best. The weather was a mixed blessing but at least kept us to the task. And the facilities were adequate, apart from rather limited access to wi-fi (this is good and bad: like the weather it took away distractions, but it also made it difficult to look up previous results). So many thanks to João for organising a memorable occasion. I should not let this post conclude without mention of Gavril Farkas, who had come because he is interested in monodromy groups of covers of surfaces; both primitivity and 2-transitivity have natural interpretations in this context, and he was looking for intermediate properties which might have similar interpretations.