Thoughts on teaching multivariable calculus

Power Overwhelming 2025-08-08

In my last semester of MIT I led a recitation (i.e. twice-a-week review) session1 for multivariable calculus (18.02) at MIT (although the first few weeks are all linear algebra). It’s different from many contexts I’ve taught in before; the emphasis of the class is on doing standard procedures, but the challenge is that there is a lot of ground covered. That is, compared to other settings I’ve taught, there is generally a tradeoff of less depth for more breadth.

This post is about what I learned about teaching in the process, formatted as advice for future recitation instructors.

Summary

If I want to capture this post into a few sound-bites to take home, here’s what I would say:

- Focus on what happens outside recitation: write things up and go the extra mile.

- Use concrete, illustrative examples.

- Be opinionated and find good sound-bites. Tell a good story.

- Repeat yourself.

- Planning is useful, but plans are useless.

1a. Write things up

Before teaching 18.02, I went through the required teacher training run by MIT’s math department. They talked a lot about things like managing board space (hint: always write more words on the board), engaging with audience questions well, delivering interactive sessions and not a monologue, and so on. Similarly, if you try to read about good teaching practices on the Internet, you’ll get a lot of advice like “active learning” or “group collaboration” or “breaking down the glass wall” and so on.

None of this advice is wrong and you should follow it. But the best advice I got was actually buried in an email I got from Larry Guth:

I wanted to quickly write back and say that there a lot of ways to help students as a TA, and some of them are more offline – like writing very clear and well-written solutions to problems from recitation. … And if you think of a better answer the evening after recitation at home – it’s not too late! You can explain it to them at the start of next recitation or you can write it up and put it somewhere they can look at if they want to.

I love this, but actually I think it’s too polite. I would go as far as to assert:

It is impossible to teach math well without having good written material. Conversely, you can do better than most instructors by ONLY writing well.

This is the same lesson I mentioned in sections 2 and 3 of my OTIS teaching post. I was curious whether the same would be true for 18.02, and the answer is yes. By the second week I would overhear students telling each other “Evan’s notes are really good” and “I love these notes so much” and so on. I can’t stress enough — when people learn something from the first time, polished documentation with the obvious-to-experts details spelled out is priceless.

As a rule of thumb, whenever a student asks me a question, I immediately ask myself: “are they asking me this because I failed to state this in writing?”. Often the answer is “yes”, and then I know I have more writing to do. Anything that’s worth saying out loud is worth writing down.

Probably it also decreased attendance at my section; it was at 9am and the students knew everything would be posted later. But my goal is to teach well, not to maximize attendance.

You can see my notes posted on my website. If you want to see just how much effort I was putting in to writing them, have a look at the commit history.

1b. Go the extra mile

The second most impactful thing I did took only a few minutes of effort. It’s a good story.

Originally, I was assigned recitation 9am-10am on Monday and Wednesday and office hours at 10am-11am on Monday. I noticed the Monday office hours was popular; people came with questions fresh in their minds. So I emailed the math department asking if I could book a room for 10am-11am on Wednesday too. Worked wonders.

I just don’t like the prevalent mindset that teaching well is mostly about steering a classroom. You’ll just miss out on big improvements like this by hyper-focusing on the classroom delivery. Becoming a good speaker is a difficult performing art; you’ll never be able to finish optimizing it. So pay attention to other things, too.

2. Use concrete, illustrative examples

The straw man is to take every theorem with variables in it and give an example where you plug in actual numbers for the variables. We can do better. Here are a few examples of examples.

Example: Linear span

One theorem we covered was that one could tell whether three vectors in were linearly independent or not by checking the determinant of the corresponding

matrix. To drive the point home, I gave the example

,

,

and made the following point explicit:

“Look, these three vectors look like they’re just random numbers, so you wouldn’t expect there to be some relation between them. However, it turns out that

You would never be able to notice these coefficients just by looking, so you need to invoke the determinant to do the work for you.”

(See Section 2 of r04.pdf to see the example in full.)

The displayed line is the punch line. “Do concrete examples” is more than just “plug in lots of numbers”. In this case, I really wanted to show that the determinant was doing some heavy lifting, giving a nontrivial shortcut. So I went out of my way to also show how big the coefficients in the linear dependence (whose existence is predicted by ) can be.

Example: Normal vectors to planes

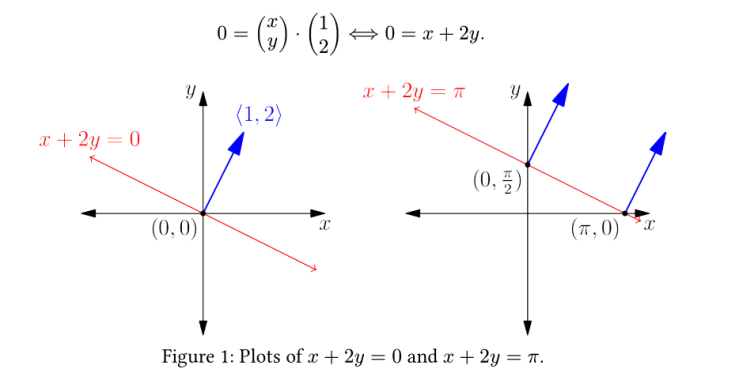

A lot of students had difficult trying to understand why the equation has normal vector

, and why the parameter

doesn’t matter. In this case, it wasn’t enough to just specialize to, say,

and its normal vector

. Plugging in numbers here didn’t help the students understand what was going on.

So to make my point come across, I had to actually go back to two dimensions, where the students could rely on school algebra intuition. MIT students know from high school that lines and

are parallel, and they can see from the picture that the normal vector

is indeed perpendicular to that line. Here’s the picture I drew in my notes for them.

Then I just said “3D is the same situation”, and it worked.2 (See Section 4 of r02.pdf to see the example in full.)

Example: Multiple normal vectors

Here’s one situation where just numbers was enough: to explain to students why normal vectors were unique only up to scaling, I would just point out that and

are equivalent3, so both

or

worked fine as normal vectors.

3. Be opinionated and find good sound-bites. Tell a good story.

It’s a mistake to think of math as a long list of definitions, theorems, and formulas; they all relate. So one way to present material better is to present it as a narrative. And a way to make strong narratives is inventing compelling sound-bite: a single sentence that you can say, over and over, to move the story forward.

For example, at the start of the class on normal vectors, I used the following:

Normal vectors replace slopes. Everything you used slopes for before, you should now think in terms of normal vectors.

This sound-bite was used a couple of times:

- It accompanied the example I gave earlier with

; the students remember that

is parallel to

.

- More generally, it gave them the instinct that anything related to the “direction” of the plane (rather than the position) should be done via normal vectors, and in particular independent of

.

- So, e.g., when the exam asks to see if two planes are perpendicular or some vector is parallel to a plane, the students will automatically reach for the right thing.

- It helped students remember that for

, the “type” of the gradient

is going to be a normal vector to the (hyper)plane, rather than a single number like the derivative was (because the derivative was thought of as a slope).

As another example, when I was teaching the basics of linear transformations, the sound-bite I used was:

If you know the output of

at every basis vector, you can extract the output of

at any other vector.

This sound-bite helped progress the story multiple times:

- It worked well for explaining how a matrix is defined: “to encode

as a matrix, write down the outputs of the

basis vectors and glue them together”. That sentence was itself a mini-sound-bite:

- A lot of 18.02 students had trouble with taking a matrix like

or

and turning it into a text description (here, “mapping the plane into a line”, and “rotate by

”). I leaned on this soundbite again, by telling them to always first look at where the basis vectors went, then use that to deduce the image of

, then to deduce the image of a random point like

, and finally try to describe what happened to a random point.

- Same thing but reversed, e.g. given a text description like “reflect around

”, explaining how to translate it into a matrix.

- A lot of 18.02 students had trouble with taking a matrix like

- This in turn helped motivate the definition of matrix multiplication, where I explicitly showed my students why matrix multiplication corresponds to function composition. (See Section 4 of r03.pdf to see this story play out.)

- By setting up the sound-bite, I could tell the following story. “This shows why the 18.700/18.701 definitions are better than the 18.02 ones. In 18.02, the recipe for matrix multiplication is a definition: here is this contrived rule about taking products of columns and rows, trust me bro. But in 18.700/18.701, the matrix multiplication recipe is a theorem.”

- This also helped me motivate what a “basis” was later on: I just pointed out the sound-bite was also true if you replaced

and

with

and

.

- By having this sound-bite set up, I could now tell the following story: “

and

is only special in that it makes the extrapolation easier to do by hand, but

and

works fine in principle too. That’s why we say

and

is also a basis for

”.

- By having this sound-bite set up, I could now tell the following story: “

- The phrase “find good sound-bites” is itself an example of a sound-bite.4

I say “opinionated” because telling stories and finding sound-bites requires you to take a stance on what the “right” way to think about things is. You are not trying to be a neutral news reporter. It’s better to find one angle you like and really hammer it home. (In fact, it turns out that “I know the instructor presented things this way, but I want to show you another angle” makes for a great memorable story. At least if used only once in a while.)

4. Repeat yourself

In programming there’s a principle called DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself). When teaching 18.02 I found I did the opposite: when speaking out loud, anything important likely needs to be repeated multiple times in multiple sessions. (Writing is a bit different.5)

I think this is what people mean by “be patient”, but I’ll be more precise. No matter how good your first explanation was, expect to be asked to repeat it later. You might feel like a broken record at times. I lost count of the number of times I said the verbatim sentence “when you multiply two complex numbers, the magnitudes multiply and the angles add”. I once had this idea that if I gave a perfect explanation of something then I’d only have to explain it once. Reality has different plans.

This section ties into the previous two sections:

- Writing is permanent storage, so anything important should be in writing so that it can be referred back to.

- This is also why sound-bites are so useful. Repeating sound-bites verbatim works well by definition; do so liberally.

5. Planning is useful, but plans are useless

Despite the substantial amount of preparation I did for every recitation, pretty much no recitation session actually went according to plan. I would say that when teaching, you should come in with a game plan and then be prepared to modify it or discard it when (not if) the need arises.

Trying to predict too far into the future what students will or will not have trouble with is like trying to write a puzzle with no testsolvers. You should try so you have a map of each day will be about, but you’ll never be able to predict 100% accurately predict this.

Examples:

- When teaching eigenvalues, I had planned an example of using eigenvalues to compute a power of a matrix. I ended up scrapping it completely once I realized that a lot of students were still having difficulty with the actual procedure of calculating eigenvectors.

- When teaching Lagrange multipliers, I incorrectly predicted that the difficulty would be on setting up the system, but in practice it turned out that the students were pretty good at getting to the system but had more trouble with the algebra step of actually solving it. That’s why in my notes there were added sections on “advice for solving systems of equations”; it was definitely not in the first draft.

- There were definitely sessions where I went over 0 of the 3-4 recitation problems the professor asked us to talk about, because just answering the questions from the students took the entire hour.

The last bullet is worth reiterating: I would advise people to prioritize answering explicit questions over any plan.

In my recitation, I got a reputation pretty early on as someone who would make sure every question asked is answered in full, even if it meant completely derailing my plan of what I intended to cover. I was initially worried that I was being too liberal by doing this (“is it really okay for me to just completely ignore the stuff the professor asked me to do?”), but the anonymous feedback I got from my students was overwhelmingly positive on this one specific item.

To some extent I actually went out of my way to intentionally derail my plans by starting every session by asking “does anyone have any questions they’d like to ask before I start?” Because I earned a reputation as someone who took questions seriously, students would actually ask a lot of the time.

6. Small tips

Miscellaneous tips and tricks for the theatrical performance aspect:

- Write more words on the blackboard.

- Any time someone asks a substantial question, repeat “the question was…” for everyone else before answering it.

- I use eye contact often and spend more time looking at the audience than the board. When answering questions, I look directly at the asker to watch their reaction.

- A showsmanship thing I used often was to ask the audience to generate numbers for me for any example I was doing. For example, if a student asks to re-explain how to check whether three vectors in

form a basis, I’d say “I’d like nine numbers from the audience” and let them populate the coordinates of the example I use.

The Bells of Saint John

Did I try too hard?

Officially, my title was “teaching assistant” (TA). I didn’t realize until after the class started how misleading this name was. It’s easy to be lulled into seeing the instructor as the star of the show, with the TA’s being minions that help with menial grunt work.

But let me tell you something you should already know: nobody learns much in a 500-person calculus lecture.

Which means recitation isn’t just a review session; it is the class. I was going to make-or-break things: if I taught badly, it would directly hurt their grades. I wasn’t just an assistant to the teacher anymore. I was the teacher.

So after my first session, I changed my mindset. My motivation became three words that I still remembered from a Doctor Who episode I saw many years ago:

- For those of you that don’t know how the system works, at MIT, 18.02 is a huge class with 400 to 500 students (mostly first-years). In order to make sure students actually get the individual attention they need (impossible during lecture), the math department also places each student in a recitation section of about 20 students each, meeting twice a week for an hour each.

- Fun aside: I always carry an umbrella on me, because I can’t be bothered to check the weather before I leave home. It came in handy for illustration. I’m no good at 3-D blackboard art, and I wanted a picture of a plane and its normal vector, and how adjusting

moved the plane.)

- In general, multiplying by powers of

and

is something I did a lot. It makes scaling-type things a lot easier to see.

- There’s a lot of recursion in this post, since I’m trying to teach teaching.

- When writing, you can be DRY by bolding or boxing important things. When typesetting a PDF, you control the physical layout of the memory. Hence, if something is important, you can label it and then refer back to that label (e.g. link to the theorem number). So for writing the DRY principle does make sense; every statement has a single canonical position on the physical printed page, and rather than literally repeating something, you link it. But when speaking out loud, you can’t do this: you have to actually repeat sentences.