The politics of tea: Spirituality, masculinity & violence in 16th-century Japan

Australian Academy of the Humanities 2024-05-21

Ōido tea bowl, “Shumi or Jūmonji,” Korea, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), 16th century, Ido ware, Ōido, h 8.0 cm, d. 14.8 cm, Mitsui Memorial Museum Collection, Tokyo

Ōido tea bowl, “Shumi or Jūmonji,” Korea, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), 16th century, Ido ware, Ōido, h 8.0 cm, d. 14.8 cm, Mitsui Memorial Museum Collection, TokyoSometime around the end of Europe’s 16th-century, a Japanese tea master, Furuta Oribe, took a Korean Ido ware tea bowl and had it smashed into four pieces.

Japan and Korea spent the last decade of the century at war, following Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s invasions of the Korean Joseon kingdom in 1592 and again in 1598. Japan’s great warlords and shoguns highly prized tea as well as the masters who conducted its ceremonies and selected appropriate items for use within them. Oribe was tea master to three military leaders in turn, Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu.

A portrait of Sen no Rikyū by Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539 – 1610). Source: Wikipedia

A portrait of Sen no Rikyū by Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539 – 1610). Source: WikipediaThe man who had taught Oribe the way of tea, known as chado, was the period’s most famous tea master, Sen no Rikyū. He had revolutionised contemporary Japanese practice, employing simple, sometimes flawed, vessels that reflected the stripped back and imperfect aesthetic of wabi-sabi.

From the mid 16th-century, Jesuit missionaries, primarily from Italy, Spain and Portugal, had arrived in Japan where they hoped to evangelise. They had observed the appreciation of tea in multiple East Asian locales. Despite its origins in Shinto and Zen Buddhist ideas, Portuguese-born Jesuit João Rodrigues found what he saw as the emotional and social discipline instilled through chado highly praiseworthy. Rodrigues reported how the leading Christian convert, daimyō Takayama Ukon, baptised Justus,

‘was wont to say, as we several times heard him, that he found suki [the tea ceremony] a great help towards virtue […] he would retire to that small [tea] house with a statue, and there according to the custom that he had formed he found peace and recollection in order to commend himself to God.'(1)

Tea & the military

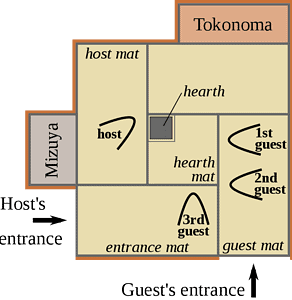

The layout of a typical tea room during the winter. Each part of the tea room has a special role in the ceremony, down to the lines of the tatami mats on the floor. Source: Wikipedia

The layout of a typical tea room during the winter. Each part of the tea room has a special role in the ceremony, down to the lines of the tatami mats on the floor. Source: WikipediaPaying close attention to the cultural codes of highly militarised Japanese society, Jesuits in Japan recognised that tea culture was favoured by the military elite, a cohort whose conversion could be highly influential. The Jesuit Visitor, who came to inspect the work of the missionaries in Japan, Alessandro Valignano, recommended that Jesuit residences should create a dedicated tea room with an attendant, freed from manual labour, who would ensure that the missionaries could offer tea and tea ware befitting the rank of their male guests. Women were not to remain longer in the room than it took to deliver their message. (2)

Towards the end of the 16th-century, these networks helped Jesuits to discern Hideyoshi’s strong interest in attacking Korea. Some were enthusiastic that the endeavour might open the Korean kingdom, hitherto closed to their evangelising work, to the Catholic mission. Others feared Hideyoshi’s hidden aim might be to limit the influence of the growing cohort of Christian military leaders by sending them out of the country.

Christian Japanese lords were indeed central to Hideyoshi’s first invasion force, where they were accompanied by a small number of Jesuits who acted as spiritual support for them and their troops. But the Jesuits made more significant inroads into conversion of Koreans among those who were forcibly taken back to Japan, mostly as enslaved labourers. In Japan, Christian missionaries offered practical and spiritual support to many forcibly displaced Koreans, and celebrated the conversion, as Portuguese Jesuit Luís Fróis wrote, of

‘these first fruits of that kingdom of Korea brought now by this war, for the greater good of their souls.’ (3)

Influencing politics & culture

Koreans with specialist skills were particularly sought after by Japanese lords. Hideyoshi directed his daimyōs to use the invasions as an opportunity to source Korean skills and talents as well as a labour force. Among those most highly prized were ceramic experts, particularly those who worked in the rustic style favoured by Japan’s leading tea masters.

Oribe, however, was not content to accept contemporary ceramic aesthetics. Yet he did not order the Korean tea bowl smashed in order to destroy it.

Instead, he had the vessel re-made, reducing it to a size he deemed more acceptable for Japanese practice, and resealed the four pieces together with red lacquer in the kintsugi technique that foregrounded and celebrated obvious damage and repair. (4) This was no longer Sen no Rikyū’s acceptance of nature as it was, including the accidental flaws of firing, but a visible re-assembling of the material world to the purposes that Oribe’s tea practice required.

Not all his contemporaries were impressed by these unconventional interventions into the aesthetics of chado. Oribe was criticised as

‘a person who defiles treasures, cutting up hanging scrolls he deems unseemly and delighting in breaking apart good teabowls.’ (5)

Ōido tea bowl, “Shumi or Jūmonji,” Korea, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), 16th century, Ido ware, Ōido, h 8.0 cm, d. 14.8 cm, Mitsui Memorial Museum Collection, Tokyo

Ōido tea bowl, “Shumi or Jūmonji,” Korea, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), 16th century, Ido ware, Ōido, h 8.0 cm, d. 14.8 cm, Mitsui Memorial Museum Collection, TokyoBut just as concerning for some was the growing influence of Christian ideas among the disciples of tea culture. (6) Jesuit attention to tea’s cultural and political power paid dividends as a growing cohort of tea masters converted to Christianity or, like Oribe, had family who were Christian.

Oribe’s smashed bowl produced a striking effect for, when viewed from above, the break points formed a cross. One of the tea bowl’s names is Jūmonji, meaning the cross.

Both Oribe’s Christian connections and his aesthetics were deemed dangerous. In 1615, he committed suicide. The politics of tea could prove deadly.

Oribe’s re-made Korean vessel stands as a reminder that, at the turn of Europe’s 17th-century, tea in its practices and ceramics marked relations between Japan, Korea, and Catholic missionaries, both as these were mired in violence and as they generated new aesthetic, spiritual and cultural expressions.

Sources: 1. Michael Cooper, S.J., “The Early Europeans and Tea,” Tea in Japan: Essays on the History of Chanoyu, eds Paul Varley and Kumakura Isao (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1989), 119. 2. Cooper, “The Early Europeans and Tea,” 105-9. 3. Susan Broomhall, Evangelizing Korean Women and Gender in the Early Modern World: The Power of Body and Text (Leeds: ARC Humanities Press, 2023), 22. 4. Record of the Jūmonji Ido tea bowl (Jūmonji Ido chawan ki 十文字井戸茶碗記) of 1727, cited in Annegret Bergman, “Keshiki in Tea Ceramics, Art Research Special Issue, Journal of the Art Research Center, Ritsumeikan University, 1, (2020): 7. 5. Misato Shōmura, catalogue entry in Turning Point: Oribe and the Arts of Sixteenth-Century Japan, ed. Miyeko Murase (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art 2003), 109. 6. Hideaki Furukawa, “The Tea Master Oribe,” in Turning Point, ed. Murase, 101.

The post The politics of tea: Spirituality, masculinity & violence in 16th-century Japan appeared first on Australian Academy of the Humanities.