Women Philosophers of the Greco-Roman World: Uncovering Some Hidden Gems

Australian Academy of the Humanities 2024-09-13

A 1847 lithograph of Caroline Herschel by G Busse. Herschel is estimated to be 97 years of age.

A 1847 lithograph of Caroline Herschel by G Busse. Herschel is estimated to be 97 years of age.Women’s intellectual contributions to the pool of human knowledge, until recent decades, have not received wide public recognition. While their numbers were few, they emerged in myriad fields overcoming considerable barriers to achieve their success. There are key examples from Europe’s early modern age such as Caroline Herschel (1750-1848), sister and assistant to the famous astronomer William Herschel, who made her own discoveries and was the first woman in Britain to receive an annual stipend from the king.

Similarly, Mary Somerville (1780-1872), a Scottish scientist, was largely self-taught in many domains, defying the general attitude summed up in her father’s comment that studying would be bad for her because “the strain of abstract thought would injure the tender female frame.”

But these were rare exceptions in areas in which privileged women had unusual opportunities for self-development and a chance to emerge from the shadow of male scientists who were liberal minded on a small scale.

Moreover, these women were by no means the first female intellectuals and astronomers. Much earlier examples of such ‘unicorns’ exist. As far back as the Greco-Roman world there were some intriguing exceptions in male-dominated fields where women busied themselves in intellectual pursuits as physicians, priests and philosophers. Women in such roles defied the conventional belief that women should be quiet and stay at home. Instead, they broke the mould, often aided by the tolerance and encouragement of a well-educated parent, usually the father. One significant reason that we now know more about such women is that we have started to take a keen interest in such cases and ask the right questions. The 2023 collection of essays edited by Katharine O’Reilly and Caterina Pellò, Ancient Women Philosophers: Recovered Ideas and New Perspectives is a clear sign of the renewed interest in female thinkers from the ancient past around the world.

Women philosophers: Aretê, Sosipatra, Hypatia & Asclepigenia

From the sixth century BCE down to the fourth century CE, we find mention of women intellectuals active in domains we would now call science and philosophy—fields that were not yet so distinct at the time. For instance, Pythagoras acknowledges that his teacher of moral doctrines was Themistokleia, a priestess in Delphi; the claim is poorly documented, but his own theories support such a connection with the Apollo sanctuary.

Aretê of Cyrene (4th-3rd century BCE) is said to have been taught by her father, the philosopher Aristippus of Cyrene, who had been a student of Socrates and the founder of the Cyrenaic school of thought (mentioned in Cicero and Pliny the Elder). Aretê (meaning ‘Virtue’) followed his ideas in Cyrenaic philosophy (known as the hedonist philosophy), which placed a central importance on pleasure as a positive outcome from morally correct behaviour. They also argued that bad behaviour would increase a person’s pain (or “mental discomfort” with feelings such as guilt, shame, or embarrassment). The Cyrenaic doctrine taught that the only intrinsic good is pleasure—a state of being in which one does not feel pain or discomfort, including feeling good about one’s choices. This principle could mean that Aristippus would not shy away from breaking social conventions. Another female philosopher was Leontion, a student of Epicurus—the latter was unusual in allowing women philosophers and slaves to attend his school. Epicurus praised her for her well-written arguments against other philosophical views: “Healer Lord, my dear Leontion, with what resounding exultation we were filled upon reading your letter.” (Diogenes Laertius X.5, tr. S. White).

In late Roman empire we find three remarkable women about whom we know more. These famous and better documented cases are from the late antique period. Sosipatra of Pergamum was highly admired by the historian Eunapius (our main source, ca. 395 CE). She surpassed most of her contemporaries (including her husband Eustathius, VPS 6.53), and was an extraordinary female philosopher who founded her own school. She was knowledgeable about Greek philosophy and eastern mystical doctrine of the Chaldeans, and so dedicated to the work that she never married.—

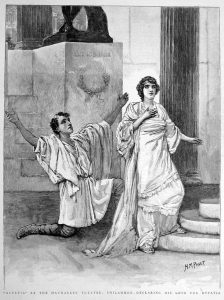

An actress plays Hypatia during a play, ‘Hypatia’ at the Haymarket Theatre. This print first appeared in a 1893 issue of ‘The Graphic’. Source: H. M. Paget

An actress plays Hypatia during a play, ‘Hypatia’ at the Haymarket Theatre. This print first appeared in a 1893 issue of ‘The Graphic’. Source: H. M. PagetNext, Hypatia, the daughter of the mathematician Theon, who had his own school of mathematics. She was his best student, and he handed his school over to her before his death, securing the continuity, at least for a time. Hypatia’s untimely and violent death at the hands of an aggressive Christian mob has echoed through the ages and led to various forms of tribute. Her teaching comprised of extensive instruction in mathematics and philosophy (Plato, Aristotle), even exploring the interplay between these domains, while striving for the Platonist goal to improve the soul and teach the range of virtues defined by Plotinus and Porphyry, the new Platonism of this period. Although little of her work survives, we have some basic information about her writings. I already mentioned the commentary, which she probably prepared with her father Theon, on the mathematical writings of Ptolemy, in particular his Almagest. She also wrote commentaries on various works in geometry and mathematics, for example, on the third-century mathematician Diophantus of Alexandria’s Arithmetica and Apollonius’ Conic Sections.

The third and last woman to mention is Asclepigenia. Edward Watts has called her one of “Hypatia’s Sisters”. She was personally trained by her father, who was a very good teacher. Asclepigenia was the teacher of the brilliant late Platonist Proclus (412-485 CE). The evidence suggests that she taught the highest levels of Platonist philosophy, focused on moral teachings and the range of virtues that the Platonists taught—a pattern common to these female thinkers.

There have always been trailblazers among women who engage in intellectual pursuits and achieve the status of ‘philosopher’.

The evidence I have surveyed is a snapshot and in no way comprehensive, but it clearly shows that female philosophers existed through all periods in ancient Greece and the Roman empire. The geographical and intellectual diversity in this sample, stretching from Alexandria to Pergamon and Greece, shows how one can contemplate the good life wherever one resides, and how one might be happy within the natural constraints of one’s life and talents. Crucially, their achievements are facilitated by generous fathers, who encouraged their daughters to take up intellectual pursuits regardless of social pressures. Such special circumstances were clearly necessary and possibly the result of the educational traditions where individual tutoring and freedom of subject matter tailored the curriculum to the student. In sum, all these exceptional women were just that, exceptions. And, as we all know, exceptions confirm the rule. Their achievements were extraordinary, and the survival of their stories confirms their intellectual contributions. Such remarkable women are a significant chapter in the history of humankind and teach us about the possibility of bucking the trend, in their cases under very difficult social conditions.

The post Women Philosophers of the Greco-Roman World: Uncovering Some Hidden Gems appeared first on Australian Academy of the Humanities.