Why Paying to Delete Stolen Data is Bonkers

Krebs on Security 2020-11-19

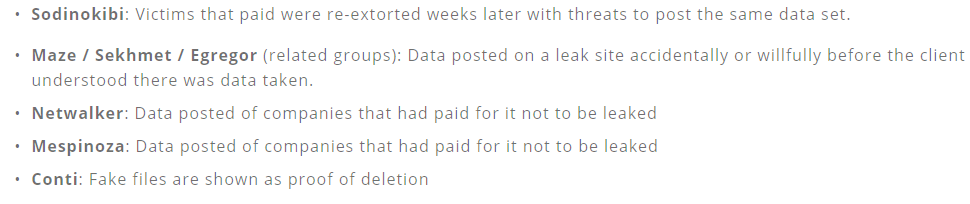

Companies hit by ransomware often face a dual threat: Even if they avoid paying the ransom and can restore things from scratch, about half the time the attackers also threaten to release sensitive stolen data unless the victim pays for a promise to have the data deleted. Leaving aside the notion that victims might have any real expectation the attackers will actually destroy the stolen data, new research suggests a fair number of victims who do pay up may see some or all of the stolen data published anyway.

The findings come in a report today from Coveware, a company that specializes in helping firms recover from ransomware attacks. Coveware says nearly half of all ransomware cases now include the threat to release exfiltrated data.

“Previously, when a victim of ransomware had adequate backups, they would just restore and go on with life; there was zero reason to even engage with the threat actor,” the report observes. “Now, when a threat actor steals data, a company with perfectly restorable backups is often compelled to at least engage with the threat actor to determine what data was taken.”

Coveware said it has seen ample evidence of victims seeing some or all of their stolen data published after paying to have it deleted; in other cases, the data gets published online before the victim is even given a chance to negotiate a data deletion agreement.

“Unlike negotiating for a decryption key, negotiating for the suppression of stolen data has no finite end,” the report continues. “Once a victim receives a decryption key, it can’t be taken away and does not degrade with time. With stolen data, a threat actor can return for a second payment at any point in the future. The track records are too short and evidence that defaults are selectively occurring is already collecting.”

The company said it advises clients never to pay a data deletion ransom, but rather to engage competent privacy attorneys, perform an investigation into what data was stolen, and notify any affected customers according to the advice of counsel and application data breach notification laws.

Fabian Wosar, chief technology officer at computer security firm Emsisoft, said ransomware victims often acquiesce to data publication extortion demands when they are trying to prevent the public from learning about the breach.

“The bottom line is, ransomware is a business of hope,” Wosar said. “The company doesn’t want the data to be dumped or sold. So they pay for it hoping the threat actor deletes the data. Technically speaking, whether they delete the data or not doesn’t matter from a legal point of view. The data was lost at the point when it was exfiltrated.”

Ransomware victims who pay for a digital key to unlock servers and desktop systems encrypted by the malware also are relying on hope, Wosar said, because it’s also not uncommon that a decryption key fails to unlock some or all of the infected machines.

“When you look at a lot of ransom notes, you can actually see groups address this very directly and have texts that say stuff along the lines of, Yeah, you are fucked now. But if you pay us, everything can go back to before we fucked you.'”