Checkout Skimmers Powered by Chip Cards

Krebs on Security 2021-02-24

Easily the most sophisticated skimming devices made for hacking terminals at retail self-checkout lanes are a new breed of PIN pad overlay combined with a flexible, paper-thin device that fits inside the terminal’s chip reader slot. What enables these skimmers to be so slim? They draw their power from the low-voltage current that gets triggered when a chip-based card is inserted. As a result, they do not require external batteries, and can remain in operation indefinitely.

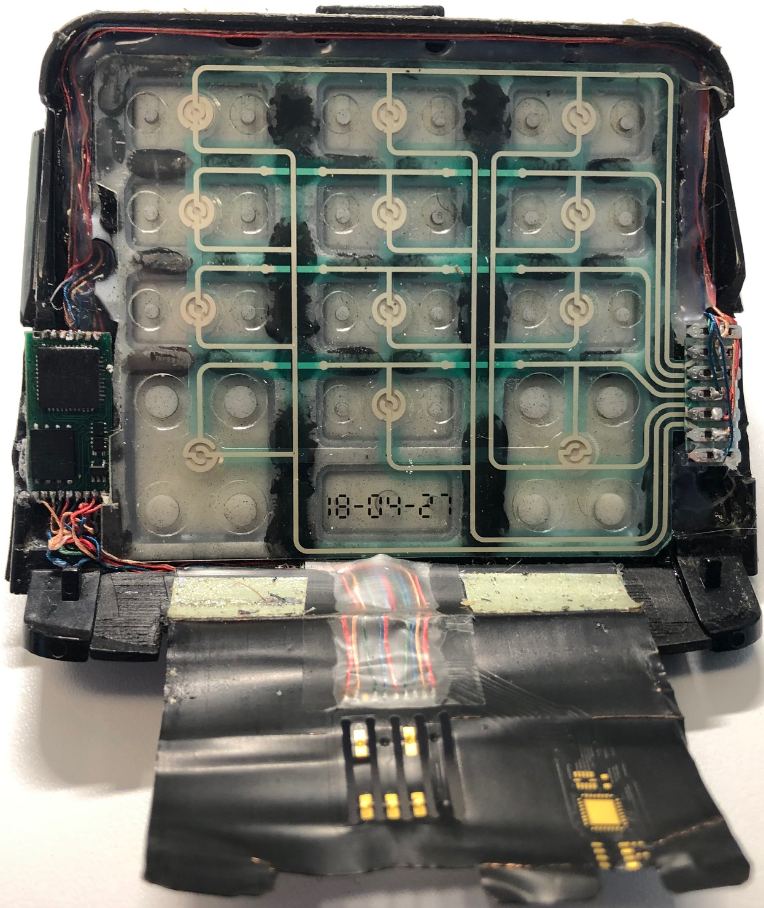

A point-of-sale skimming device that consists of a PIN pad overlay (top) and a smart card skimmer (a.k.a. “shimmer”). The entire device folds onto itself, with the bottom end of the flexible card shimmer fed into the mouth of the chip card acceptance slot.

The overlay skimming device pictured above consists of two main components. The one on top is a regular PIN pad overlay designed to record keypresses when a customer enters their debit card PIN. The overlay includes a microcontroller and a small data storage unit (bottom left).

The second component, which is wired to the overlay skimmer, is a flexible card skimmer (often called a “shimmer”) that gets fed into the mouth of the chip card acceptance slot. You’ll notice neither device contains a battery, because there simply isn’t enough space to accommodate one.

Virtually all payment card terminals at self-checkout lanes now accept (if not also require) cards with a chip to be inserted into the machine. When a chip card is inserted, the terminal reads the data stored on the smart card by sending an electric current through the chip.

Incredibly, this skimming apparatus is able to siphon a small amount of that power (a few milliamps) to record any data transmitted by the payment terminal transaction and PIN pad presses. When the terminal is no longer in use, the skimming device remains dormant.

The skimmer pictured above does not stick out of the payment terminal at all when it’s been seated properly inside the machine. Here’s what the fake PIN pad overlay and card skimmer looks like when fully inserted into the card acceptance slot and viewed head-on:

The insert skimmer fully ensconced inside the compromised payment terminal. Image: KrebsOnSecurity.com

Would you detect an overlay skimmer like this? Here’s what it looks like when attached to a customer-facing payment terminal:

The PIN pad overlay and skimmer, fully seated on a payment terminal.

REALLY SMART CARDS

The fraud investigators I spoke with about this device (who did so on condition of anonymity) said initially they couldn’t figure out how the thieves who plant these devices go about retrieving the stolen data from the skimmer. Normally, overlay skimmers relay this data wirelessly using a built-in Bluetooth circuit board. But that also requires the device to have a substantial internal power supply, such as a somewhat bulky cell phone battery.

The investigators surmised that the crooks would retrieve the stolen data by periodically revisiting the compromised terminals with a specialized smart card that — when inserted — instructs the skimmer to dump all of the saved information onto the card. And indeed, this is exactly what investigators ultimately found was the case.

“Originally it was just speculation,” the source told KrebsOnSecurity. “But a [compromised] merchant found a couple of ‘white’ smartcards with no markings on them [that] were left at one of their stores. They informed us that they had a lab validate that this is how it worked.”

Some readers might reasonably be asking why it would be the case that the card acceptance slot on any chip-based payment terminal would be tall enough to accommodate both a chip card and a flexible skimming device such as this.

The answer, as with many aspects of security systems that decrease in effectiveness over time, has to do with allowances made for purposes of backward compatibility. Most modern chip-based cards are significantly thinner than the average payment card was just a few years ago, but the design specifications for these terminals state that they must be able to allow the use of older, taller cards — such as those that still include embossing (raised numbers and letters). Embossing is a practically stone-age throwback to the way credit cards were originally read, through the use of manual “knuckle-buster” card imprint machines and carbon-copy paper.

“The bad guys are taking advantage of that, because most smart cards are way thinner than the specs for these machines require,” the source explained. “In fact, these slots are so tall that you could fit two cards in there.”

IT’S ALL BACKWARDS

Backward compatibility is a major theme in enabling many types of card skimming, including devices made to compromise automated teller machines (ATMs). Virtually all chip-based cards (at least those issued in the United States) still have much of the same data that’s stored in the chip encoded on a magnetic stripe on the back of the card. This dual functionality also allows cardholders to swipe the stripe if for some reason the card’s chip or a merchant’s smartcard-enabled terminal has malfunctioned.

Chip-based credit and debit cards are designed to make it infeasible for skimming devices or malware to clone your card when you pay for something by dipping the chip instead of swiping the stripe. But thieves are adept at exploiting weaknesses in how certain financial institutions have implemented the technology to sidestep key chip card security features and effectively create usable, counterfeit cards.

Many people believe that skimmers are mainly a problem in the United States, where some ATMs still do not require more secure chip-based cards that are far more expensive and difficult for thieves to clone. However, it’s precisely because some U.S. ATMs lack this security requirement that skimming remains so prevalent in other parts of the world.

Mainly for reasons of backward compatibility to accommodate American tourists, a great number of ATMs outside the U.S. allow non-chip-based cards to be inserted into the cash machine. What’s more, many chip-based cards issued by American and European banks alike still have cardholder data encoded on a magnetic stripe in addition to the chip.

When thieves skim non-U.S. ATMs, they generally sell the stolen card and PIN data to fraudsters in Asia and North America. Those fraudsters in turn will encode the card data onto counterfeit cards and withdraw cash at older ATMs here in the United States and elsewhere.

Interestingly, even after most U.S. banks put in place fully chip-capable ATMs, the magnetic stripe will still be needed because it’s an integral part of the way ATMs work: Most ATMs in use today require a magnetic stripe for the card to be accepted into the machine. The main reason for this is to ensure that customers are putting the card into the slot correctly, as embossed letters and numbers running across odd spots in the card reader can take their toll on the machines over time.

And there are the tens of thousands of fuel pumps here in the United States that still allow chip-based card accounts to be swiped. The fuel pump industry has for years won delay after delay in implementing more secure payment requirements for cards (primarily by flexing their ability to favor their own fuel-branded cards, which largely bypass the major credit card networks).

Unsurprisingly, the past two decades have seen the emergence of organized gas theft gangs that take full advantage of the single weakest area of card security in the United States. These thieves use cloned cards to steal hundreds of gallons of gas at multiple filling stations. The gas is pumped into hollowed-out trucks and vans, which ferry the fuel to a giant tanker truck. The criminals then sell and deliver the gas at cut rate prices to shady and complicit fuel station owners and truck stops.

A great many people use debit cards for everyday purchases, but I’ve never been interested in assuming the added risk and pay for everything with cash or a credit card. Armed with your PIN and debit card data, thieves can clone the card and pull money out of your account at an ATM. Having your checking account emptied of cash while your bank sorts out the situation can be a huge hassle and create secondary problems (bounced checks, for instance).

The next skimmer post here will examine an inexpensive and ingenious analog device that helps retail workers quickly check whether their payment terminals have been tampered with by bad guys.