The Fake Browser Update Scam Gets a Makeover

Krebs on Security 2023-10-18

One of the oldest malware tricks in the book — hacked websites claiming visitors need to update their Web browser before they can view any content — has roared back to life in the past few months. New research shows the attackers behind one such scheme have developed an ingenious way of keeping their malware from being taken down by security experts or law enforcement: By hosting the malicious files on a decentralized, anonymous cryptocurrency blockchain.

In August 2023, security researcher Randy McEoin blogged about a scam he dubbed ClearFake, which uses hacked WordPress sites to serve visitors with a page that claims you need to update your browser before you can view the content.

The fake browser alerts are specific to the browser you’re using, so if you’re surfing the Web with Chrome, for example, you’ll get a Chrome update prompt. Those who are fooled into clicking the update button will have a malicious file dropped on their system that tries to install an information stealing trojan.

Earlier this month, researchers at the Tel Aviv-based security firm Guardio Labs said they tracked an updated version of the ClearFake scam that included an important evolution. Previously, the group had stored its malicious update files on Cloudflare, Guard.io said.

But when Cloudflare blocked those accounts the attackers began storing their malicious files as cryptocurrency transactions in the Binance Smart Chain (BSC), a technology designed to run decentralized apps and “smart contracts,” or coded agreements that execute actions automatically when certain conditions are met.

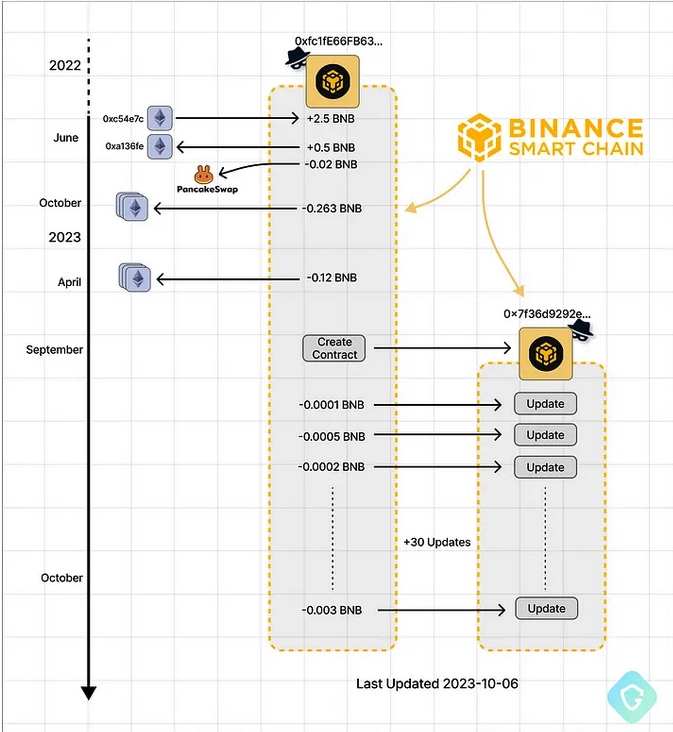

Nati Tal, head of security at Guardio Labs, said the malicious scripts stitched into hacked WordPress sites will create a new smart contract on the BSC Blockchain, starting with a unique, attacker-controlled blockchain address and a set of instructions that defines the contract’s functions and structure. When that contract is queried by a compromised website, it will return an obfuscated and malicious payload.

“These contracts offer innovative ways to build applications and processes,” Tal wrote along with his Guardio colleague Oleg Zaytsev. “Due to the publicly accessible and unchangeable nature of the blockchain, code can be hosted ‘on-chain’ without the ability for a takedown.”

Tal said hosting malicious files on the Binance Smart Chain is ideal for attackers because retrieving the malicious contract is a cost-free operation that was originally designed for the purpose of debugging contract execution issues without any real-world impact.

“So you get a free, untracked, and robust way to get your data (the malicious payload) without leaving traces,” Tal said.

Attacker-controlled BSC addresses — from funding, contract creation, and ongoing code updates. Image: Guard.io.

In response to questions from KrebsOnSecurity, the BNB Smart Chain (BSC) said its team is aware of the malware abusing its blockchain, and is actively addressing the issue. The company said all addresses associated with the spread of the malware have been blacklisted, and that its technicians had developed a model to detect future smart contracts that use similar methods to host malicious scripts.

“This model is designed to proactively identify and mitigate potential threats before they can cause harm,” BNB Smart Chain wrote. “The team is committed to ongoing monitoring of addresses that are involved in spreading malware scripts on the BSC. To enhance their efforts, the tech team is working on linking identified addresses that spread malicious scripts to centralized KYC [Know Your Customer] information, when possible.”

Gaurdio says the crooks behind the BSC malware scheme are using the same malicious code as the attackers that McEoin wrote about in August, and are likely the same group. But a report published today by email security firm Proofpoint says the company is currently tracking at least four distinct threat actor groups that use fake browser updates to distribute malware.

Proofpoint notes that the core group behind the fake browser update scheme has been using this technique to spread malware for the past five years, primarily because the approach still works well.

“Fake browser update lures are effective because threat actors are using an end-user’s security training against them,” Proofpoint’s Dusty Miller wrote. “In security awareness training, users are told to only accept updates or click on links from known and trusted sites, or individuals, and to verify sites are legitimate. The fake browser updates abuse this training because they compromise trusted sites and use JavaScript requests to quietly make checks in the background and overwrite the existing website with a browser update lure. To an end user, it still appears to be the same website they were intending to visit and is now asking them to update their browser.”

More than a decade ago, this site published Krebs’s Three Rules for Online Safety, of which Rule #1 was, “If you didn’t go looking for it, don’t install it.” It’s nice to know that this technology-agnostic approach to online safety remains just as relevant today.