Do the Cthulhu: Monsters and Cannibals

Waggish 2021-10-31

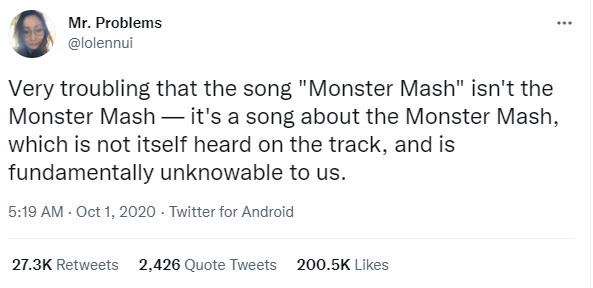

It is a truth universally acknowledged that no one knows how to do the Monster Mash, and that the song only describes people doing the dance and not how to dance it.

Yet the Monster Mash can be known. Its own lyrics say as much. The cost—one’s sanity, surely—may just be too great.

For you, the living, this mash was meant too When you get to my door, tell them Boris sent you

Then you can monster mash (The monster mash) And do my graveyard smash (Then you can mash) You’ll catch on in a flash (Then you can mash) Then you can monster mash

Monster Mash (Bobby Pickett)

The Monster Mash describes a realm in which those who know do and those who do know, a realm in which a “flash” will immediately grant you the terrible knowledge both of the dance and of the creatures who perform it and their realm. Once one sees beyond the veil, once one crosses beyond the threshold of Pickett’s “door” of perception, there is no turning back.

Outside the ordered universe that amorphous blight of nethermost confusion which blasphemes and bubbles at the center of all infinity—the boundless daemon sultan Azathoth, whose name no lips dare speak aloud, and who gnaws hungrily in inconceivable, unlighted chambers beyond time and space amidst the muffled, maddening beating of vile drums and the thin monotonous whine of accursed flutes.

H. P. Lovecraft, “The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath“

That flash of Lovecraftian gnosis, in less macabre presentations, is central to the history of dance crazes more generally. Despite the Swingers’ egalitarian claim that it ain’t what you dance, it’s the way you dance it, the privileged knowledge of dance moves has been central to the history of musical exhortations to hit the dancefloor. As with so many in-group declarations (Actor’s Equity, say), the only way to become a member is to already be a member.

The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band captured this paradox in their 1969 performance, in which Viv Stanshall describes a mash that has not yet taken place. As the monsters wake up and begin to dance, the temporal paradox causes the song to self-destruct at the very moment Stanshall begins the countdown to the actual mash:

“The countdown begins now…”The song becomes its own sequel, in the style of Christopher Priest’s The Affirmation.

The Monster Mash is atypical in not being explicitly prescriptive. It hints at what is behind the veil but only offers a polite invitation and a seductive peek. Most songs about dances do indeed exhort the listener to perform their titular dance, and many go further by shaming those ignorant of the moves, drawing a line between populist inclusiveness (everyone can do this dance!) and elitist exclusion (if you don’t do this dance, you are a loser!)

Now here’s a dance you should know! When the lights are down low! Grab your baby, then go! Do the Hucklebuck, do the Hucklebuck If you don’t know how to do it Then you’re out of luck! Shove your baby in, twist her all around Then you start a twisting mad and moving all around Wiggle like a snake, waddle like a duck That’s what you do when you do the Hucklebuck

The Hucklebuck (Roy Alfred, lyricist)

The song berates the listener for not already knowing the Hucklebuck, as a precursor to the actual instruction. The promise of secret knowledge lures in listeners, and a line is drawn between the elect and the hoi polloi. (The Fall, at the peak of Mark E. Smith’s obsession with H. P. Lovecraft, would ridicule this pretense to exclusive coolness by rewriting it as “Hassle Schmuck”.)

In the classic Honeymooners episode “Young at Heart,” Ralph Kramden hears the song exactly once, after which he somehow has acquired that elect knowledge and can mysteriously dance fluidly and confidently. Ralph has crashed through the barriers separating him from Jackie Gleason and Gleason’s other characters and momentarily partakes of their knowledge. Unusually for the show, Ralph wins over Alice with his new knowledge. He conquers his momentary humiliation when Alice sees him dancing, and she symbolically accepts his pin to join him inside the circle of dance knowledge, so he can continue to revel in his sudden gnosis:

“This is one of those numbers that tells a story.”Once subject to revelation (to apocalypse, literally “uncovering”), there is no turning back. Not even Alice Kramden can manage it. She too succumbs.

M. T. Anderson, author of Symphony for the City of the Dead and The Pox Party, has traced this rhetorical apocalypse back to very early in the recorded era (as well as to the envoys of Dante’s Vita Nuova):

Let’s examine the question of the division between dance and song (and lyric). Take the Charleston, for example:

Caroline, Caroline, At last they’ve got you on the map With a new tune, a funny blue tune, with a peculiar snap! You many not be able to buck and wing Fox-trot, two-step, or even swing If you ain’t got religion in your feet You can do this prance and do it neat… Charleston! Charleston! …

Like “The Monster Mash,” it slurs the difference between the dance and the song (i.e. itself) which elicits the dance. They both posit somehow an imaginary song and moment, anterior to themselves, when the dance becomes wildly popular — as if the dance proceeded the song, and the song merely announces, like John the Baptist at the river, the glory of another mover and shaker. But in fact, in each of these cases, the song is the appropriate vehicle for the dance. The song exists in a loop of self-promotion, declaring a past triumph that cannot have come before itself, the express vehicle of the dance — because you dance the Charleston to the “Charleston,” the monster mash to “The Monster Mash.” It is fundamentally unlike, say, the waltz, which can be danced to any one of a thousand waltzes, or indeed anything in 3/4 time.

This circularity, I think, is an excellent example of the Kardashian effect, a phenomenological moebius bootstrapping in which your fame comes only from announcing your fame. It is a fame simulacrum with an empty core, pointing back at an event which was not an event, deixis without a referent; an ouroboros conga line.

M. T. Anderson

Yet as the Swingers suggested, there’s always been an egalitarian, anti-gnostic tendency, taken to an extreme by the much-covered Land of 1000 Dances (Cannibal & The Headhunters, Wilson Pickett, and many others), which casually rattles off dance names in its lyrics, making it simultaneously parasitic on the others it cites (as there is no actual Land of 1000 Dances dance) and utilitarian.

Children, go where I send you (Where will you send me?) I’m gonna send you to that land The land of a thousand dances

Got to know how to Pony Like “Bony Maronie” You got to know how to Twist Goes like this

Mashed Potato Do the Alligator Twist, twister Like your sister

Then you get your Yo-Yo Say, hey, let’s go-go Get out on your knees Do the Sweet Peas

Roll over on your back Say, “I Like It Like That” Do the Watusi Do the Watusi

Then you do the Fly With the Hand Jive Then you do the Slop The Chicken and the Bop

Then you do the Fish Slow, slow Twist Then you do the Flow Got to move solo Then you do the Tango Takes two to Tango

Land of 1000 Dances (Chris Kenner)

Here is a song to which you can do every dance! You must dance the waltz to any waltz, where no other 3/4 dances are available, but you can dance any dance to Land of 1000 Dances (save the waltz). Ignorance is not a problem: do whatever dance you want, and you’re in luck no matter what. Kenner is thorough, but Cannibal and the Headhunders dropped over half of the dance names, illustrating just how irrelevant the specific dance moves were.

Na na-na na naaaaaaaYet from flattening nondifferentiation inevitably arises the urge to differentiate, and this populist trend did not last. It took the arch-romantic Bryan Ferry to fight back against the democratizing power of the Land of 1000 Dances. He posited a dance so simultaneously ubiquitous and inaccessible that knowledge and performance were reserved for those touched by the demiurge of creativity and genius: the Strand. Ferry goes further: the Strand is not a dance, but “a danceable solution,” a Platonic meta-dance that subsumes all (and exclusively) cool content, not merely dances.

Not Terry WoganIn the end, Ferry proclaims that all concreta, whether dances, flowers, or paintings, fall away before the abstractum of the Strand:

There’s a new sensation A fabulous creation A danceable solution To teenage revolution Do the Strand love When you feel love It’s the new way That’s why we say Do the Strand!

Do it on the tables Quaglino’s place or Mabel’s Slow and gentle Sentimental All styles served here Louis Seize he prefer Laissez-faire Le Strand Tired of the tango Fed up with fandango Dance on moonbeams Slide on rainbows In furs or blue jeans You know what I mean Do the Strand!…Oooh

Had your fill of Quadrilles The Madison and cheap thrills Bored with the Beguine The samba isn’t your scene They’re playing our tune By the pale moon We’re incognito Down the Lido And we like the Strand.

Arabs at oasis Eskimos and Chinese If you feel blue Look through Who’s Who See La Goulue And Nijinsky Do the Strandsky.

Weary of the Waltz And mashed potato schmaltz Rhododendron Is a nice flower Evergreen It lasts forever But it can’t beat Strand power The sphinx and Mona Lisa Lolita and Guernica Did the Strand

Do the Strand (Bryan Ferry)

The Strand’s form can inhabit a wide variety of content, but only content meeting forever-unspecified conditions of total coolness. There’s no teaching the Strand; those who can partake of it do so through some unconditioned gnostic revelation. Some will never and can never know the Strand.

But perhaps they are better off. Cthulhu knew the Strand too.

The punk era atomized the tension between elitism and populism, often by just ignoring it, but occasionally subverting it. Aside from the singular Fall example above, Cabaret Voltaire’s “Do the Mussolini (Headkick)” turns the exhortation into an ambiguous incitement to actual violence, playing on the ambiguity of that most general verb “to do.” Similarly, A Certain Ratio’s “Do the Du” takes an excellent, funky groove and puts lyrics of intimate agony on top of it which seem to have nothing to do with dancing.

The way I read it, doing the “Du” (“you”) is indeed a gnosis, but one of mutual annihilation between two partners locked into each other and away from the world. Dancing to it is running the risk of entering that nightmare. It’s the Monster Mash all over again, except the monsters are two ordinary lovers.

The ultimate riposte to the whole song-and-dance dilemma, though, is The Table’s “Do the Standing Still (Classics Illustrated),” a dance that is not a dance, one performed by corpses to a lyrical bed of quotes from Silver Age Marvel comics, a tribute to all those misfits who stay home from discos in their rooms at night reading Jack Kirby.

It’s the real monster mash.

APPENDIX:

Songs for further reference:

- The Terminals, “Do the Void”

- The Method Actors, “Do the Method”

- The Homosexuals, “Do the Total Drop”

- Electric Six, “Newark Airport Boogie”

- Kontakt Mikrofon Orkestra, “Do the Residue”

- XTC, “Traffic Light Rock”