Around the world, media outlets and journalists are using chat apps to spread the news » Nieman Journalism Lab

thomwithoutanh's bookmarks 2016-08-08

Summary:

hatsApp, on the other hand, has thus far remained set on being a very simple chat service. This means that users on WeChat are more likely to click links, while users on WhatsApp are more likely to comment and engage, and videos are more likely to go viral. Barot’s two-week attempt at reaching a South African audience on Mxit — an app that appeals to the country’s younger, poorer market because it’s free and works on feature phones2 — was somewhat different. The BBC doesn’t have nearly as large an editorial outfit in South Africa as it does in India, which meant they were more strapped to come up with relevant content. “The plan was to try and see if we could engage a younger South African audience around content that BBC News was publishing and engaging them with comments and interactive elements within the app,” he says. As it turned out, the app ended up driving BBC content as much as the other way around. Throughout the election, the dominant narrative in South Africa was that the top issues for voters were security and health. But a Mxit poll built by Barot’s team suggested otherwise — 65 percent of respondents said jobs were the key issue, while 25 percent said education was. That finding turned into additional BBC reporting. Styli Charalambous, publisher and CEO of the Daily Maverick in Johannesburg, says their experiments using Mxit have met with success, and points out that in South Africa the second most popular brand on Mxit is a publisher, 24.com. Mxit “allows you to plug in an RSS feed and is essentially a new way to reach a different (younger) audience than we would normally be exposed to,” Charalambous writes. “Some of the bigger publishers are able to reach audience sizes that match or exceed their website traffic through Mxit.”

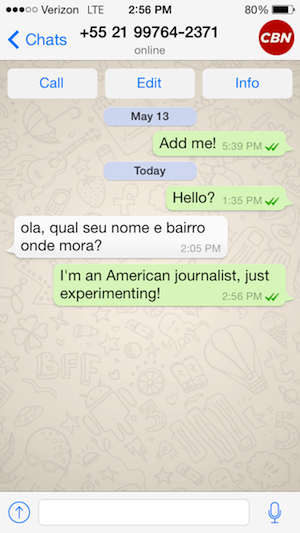

While journalists on chat apps in China are restricted by authorities, in Brazil, reporters are using them to wring transparency from their government. Juliana Duarte is a journalist with CBN radio in Brazil. The CBN website actively promotes the organization’s WhatsApp account, which they use to communicate with readers. (It’s not simple to follow a brand on WhatsApp — you have to get the phone number for the account, add it as a contact, and send a message before you receive updates.)

Duarte says the CBN audience loves to communicate by WhatsApp, especially when there’s a chance they might end up being interviewed on air. “They never stop, it’s incredible — we get messages at 1 a.m. or midnight,” she says. “Sometimes we have so many, we don’t see one message, and the person is mad!”

But all that messaging isn’t just mindless chatter. CBN listeners have repeatedly broken news for the station. In one instance, a listener sent a photo from their car of a fish that had fallen out of the sky — out of a bird’s mouth, it turned out — that was very popular online. Another time, a driver reported seeing a car plunge from Brazil’s famous Rio-Niteroi Bridge. “We thought it was impossible, but it was true — a driver saw the accident,” Duarte says.

But the most valuable use of WhatsApp by far, she says, is when listeners report shootings. “If there’s a gun shooting in the neighborhood, we receive about five messages from people saying the same thing, so we know it’s true. We call the police and say, We know about the shooting. And the police say, I don’t know. But we know, because we have messages saying that,” Duarte says. Duarte emphasized that CBN never publishes information they receive on CBN without verifying it, via interview, additional reporting, or photograph. Duarte says the newspaper Extra also uses WhatsApp, and the CBN station in Sao Paulo will soon begin using it in their newsroom as well.